The square is buzzing in central Reval, the oldest capital in northern Europe. It is the winter of 1530. The weather vane modeled after the peasant guard Thomas whirrs cheerfully with the winds of change; snow ices the rooftops. Once again, per the tradition followed for nine decades, the Town Hall has a special guest – a bedecked fir tree towering high to rival the surrounding buildings. Music weaves across the crowd, and people start to dance around the tree. Revali Raeapteek, the pharmacy, is selling its famous claret wine,[[1]] and marzipan for those who can afford the treat. There is food and laughter and merriment.

And then the tree is set on fire.

Bright Reval Midwinters

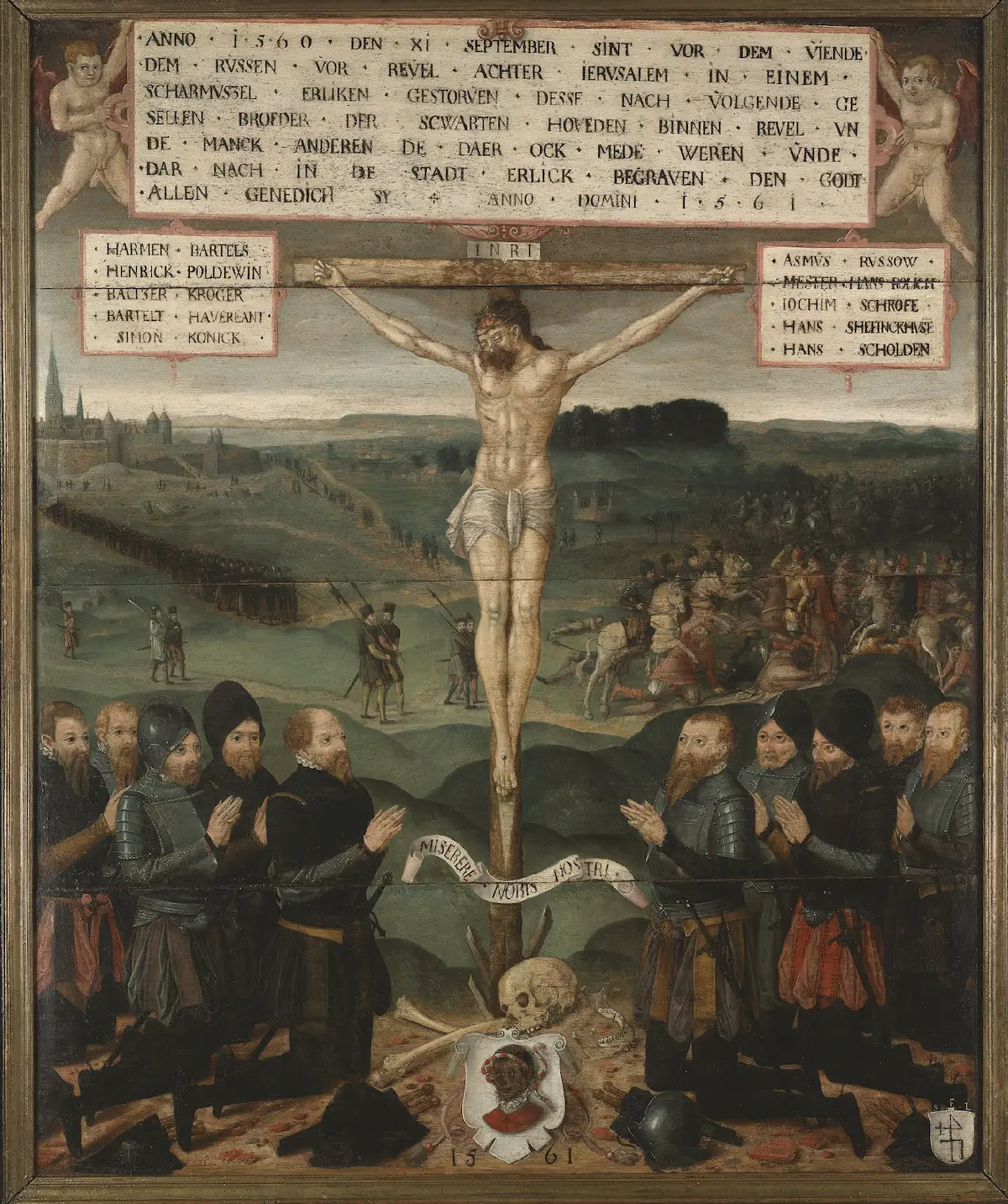

In the 15th century, the Brotherhood of the Blackheads – a guild from Germany for bachelor merchants – erected a tree during the holidays within their brotherhood hall. On the last day of festivities, the tree would be relocated to the town squares in Tallinn (Reval) and Riga, the site of dancing and festivities, and eventual bonfire. Documented evidence dates this public tradition back to at least 1441 in Reval's Town Hall (Raekoda), and it is considered the first record of a public Christmas tree in Europe, though Riga vehemently disagrees.[[2]]

This was a period before Christmas was known by that name, or celebrated as a Christian festival. The merriment was, in fact, to honour the winter season, marked by the pre-Christian pagan midwinter festival known as Jõulud, a word of Scandinavian origin from the Old Norse jul or yule, or talvistepüha (winter holiday). The solstice celebration marked the lengthening of days after the “birth of the sun", as well as the annual turnover. Historically, churches often repurposed existing holidays to absorb and alter pagan traditions. Even now in Estonia, Christmas denotes the birth of Jesus as well as the entire holiday period as a nod to its origins.[[3]]

Noisy activities were banned to encourage positive visits from spirits.

The traditional holiday period began on 21 December, or St. Thomas's Day, and ended on 6 January, known as Epiphany or Three Kings Day. Straw was a central part of the traditions for the peasantry. Large amounts of straw were brought into homes – referencing the story of Christ's birth – throughout this period in a practice known as Jõuluõled. Straw or reeds were also woven into Jõulukroon (crowns), intricate mobiles adorned with feathers or bows and hung from rafters, mimicking aristocratic glass chandeliers and candlesticks for good fortune. Meat and ale were prepared, and noisy activities were banned to encourage positive visits from spirits.

On 24 December, families would clean their homes and visit the sauna for purification, followed by a feast of abundance with seven to twelve distinct dishes for prosperity for the year ahead. Verivorst or blood sausages were customary, along with pork and sauerkraut – though this could vary in coastal regions. Home-brewed koduõlu ale and mead were also served, and a Christmas barrow bread was baked and offered to the family and farm animals. The food and fire would remain overnight in honour of ancestors and spirits, which were believed to make an appearance for the occasion; fortune-telling reading the night sky was also common.

Visits and merrymaking were common until New Year's Eve, with work being lighter during the holidays. On the last day, straw was taken back out – often men were tasked with “chasing away” the holidays with straw whips – visits were made and games were played, and the last of the food and ale prepared for the holidays was happily consumed.

Tannenbaum and Transformation

For a young Jürgen Polman, Christmases probably looked slightly different. Growing up in a Padise at war,[[4]] he would be familiar with the monastery-turned-fortress, and the constant presence of various enemy forces. The descendents of a noble Baltic German family, the Polmans in Livonia can be traced back at least to the 16th century – a time coinciding with the advent of Lutheranism in Germany, which seeped into erstwhile Estonia soon after.[[5]]

Among the changes introduced by Martin Luther in Germany in the 1530s were the focus on family rather than social or community-oriented celebrations, the abolishment of the Saint Nicholas feast in favour of the present-bearing Christkind (Christ Child, also spelled Christkindl), and eventually, moving the festivities from Christmas Day to Christmas Eve.[[6]] While Livonia still had its public square traditions, soon the plays and celebrations that took place there moved behind the doors of guilds. One such building was the Great Guild Hall in Reval, a Gothic building completed in 1410 and now housing the Estonian History Museum.

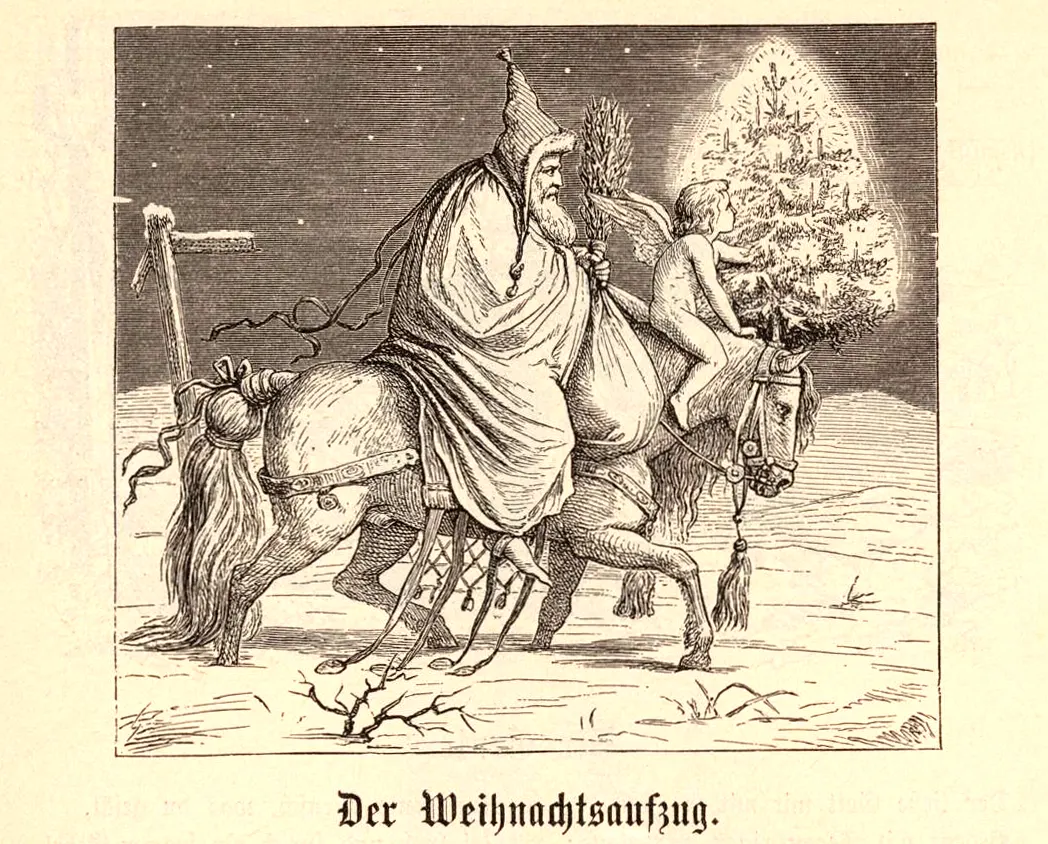

The Polmans were likely converts to Lutheranism. Hans Polman, county clerk in Padise, would have witnessed these transformations firsthand, while Jürgen, born around the mid-16th century or later, grew up with them. Perhaps they observed an amalgamation of local, German and Lutheran traditions. Lutheranism also shifted the evergreen tree decorated with apples – reminiscent of the tree in Paradise, and later known as the Tannenbaum – as well as wax candles, nuts, gingerbread, and paper roses, from the public square into guilds in late 16th century or early 17th century Germany.

Don’t want to miss the next chapter?

Become a Member of Polmanarkivet for free to get new research and stories delivered directly to your inbox the moment it's published.

A Time for Family

Jürgen's five children – sons Joran, Claus, Henrik Johan and Fredrik, and daughter Katarina – were born between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, when Lutheran traditions had been prevalent for a while. By this time, their celebration would be on Christmas Eve (Heiligabend), and Jürgen would wait until then to give his children gifts – not himself, of course, but through Jõuluvana, the Estonian Santa Claus dressed in earthy shades, or Christkind, after the Lutheran German tradition.

Legend has it that female visitors would have men's trousers or boots tied around their neck to counter ill effects.

Their Christmas feast would perhaps incorporate some German delicacies such as Lebkuchen, or gingerbread, and Stollen. After bathing at the sauna and feasting at home, Jürgen and his sons would visit the neighbours. This was an aspect of both Livonian and German traditions, called Christbaumloben in the latter, literally translated as “praising the Christmas tree”. In Livonian culture, visits from women were considered unlucky; legend has it that female visitors would have men's trousers or boots tied around their neck to counter ill effects.[[7]]

December would be festive and reflective. Advent, a German family tradition, would be marked with candles – a way to gather the whole family to observe the ritual. For children, formerly 5 December used to be a day for gifts. They would leave polished boots outside for St. Nicholas, a Catholic saint, to fill to the brim with presents, nuts and sweets. However, Lutheranism diminished the significance of the saints, instead introducing the angelic Christkind who would bring gifts on Christmas Eve. These were often new clothes and shoes for the church service. The St. Nicholas feast was also abolished.

Later, perhaps when Jürgen’s children were slightly older, there was also Krampus, or Knecht Rupprecht, to provide balance. The antagonist to Christkind, the devilish coal sack-bearing Krampus was intended to ensure good behaviour, and was believed to be equipped with a switch to whip naughty children. A visit from Krampus meant bits of coal in their shoes instead of presents.

Last Christmas

The Christmas of 1786, however, she probably hoped to forget; she was fleeing her abusive husband [...] and received help and protection from none other than Catherine the Great.

More than a century later, a German princess would find herself in Livonia. Auguste of Brunswick had spent festive Christmases in Germany and at the Russian court, but harsh ones too, on the treacherous road to Brunswick with her newborn and without her husband. The Christmas of 1786, however, she probably hoped to forget; she was fleeing her abusive husband, who had plotted to have her disgraced, and received help and protection from none other than Catherine the Great. Preparations to send her to the estate of Lohde in Livonia were already being made the day after Christmas, where she would remain – having left her children reluctantly behind, as well as most of her belongings – for slightly over a year until her death.

On the morning of 30 December, a small cavalcade of converted carriages left the dark, wintry city. They slid fast over the snow, covering the 450 km to Pernau in six days. Conversation must have been uncomfortable: a group of assorted strangers suddenly found themselves joined in a mutual future by the will of the Empress.[[8]]

Much transpired in the following year, most of it unexpected. What was meant to be a temporary relocation became a permanent exile; resigned, Auguste had come to see Lohde as home, and her companions as her chosen family, with whom she felt comfortable and safe. Among them were Reinhold Wilhelm von Pohlmann, Auguste's custodian as entrusted by Catherine, who was of noble Baltic German descent. His daughters, of a similar age, frequented Lohde. She had left the social life of the court behind, preferring a “philosophical life in the country”,[[9]] and homely pastimes such as reading, drawing, music and sewing.

By the winter of 1787, all was not well with Auguste. Though a winter house had been prepared in Reval, and Catherine was urging her to experience the sparkle of the city, Auguste didn't leave Lohde. An earlier trip in October had left her disenchanted, and she was ill – physically and most likely in mind too – in a castle largely isolated, surrounded by frigid countryside. However, “Pohlmann was taking care of the Princess like a father; he and Madame Wilde, her companions, were doing all they could to lighten her solitude.”[[10]]

Everyone imagined that Auguste had to be miserable, but her own letters consistently professed satisfaction with her new situation. While she may not have been entirely honest with Catherine, her benefactor, she had no reason to lie to her supportive mother:

“It seems to me the happiest future I could expect, free from the malice and spitefulness of the Prince and his family. I have become so accustomed to the solitude, that it will be easy for me to live like this forever. I shall have all my wishes answered if you, my dear mother, would approve my choice. It seems to me the best option for the moment to live far from the big world.”[[11]]

Perhaps for that Christmas, at least, Auguste was able to leave her troubles behind. Her chosen family would surely have prepared a small celebration, something for her to anticipate and participate in. There may have been a table adorned with what food they could afford; as its centerpiece, a golden roast, interspersed with some local cuisine. There would be nods to their shared German heritage in the lighting of advent candles, and a beautifully adorned Christmas tree – which had begun to be seen within homes in the 18th century – as well as delicious Stollen and Lebkuchen[[12]] to pass around. Perhaps they exchanged little, thoughtful gifts and books and light conversation around the fireplace. For a young woman whose life had so much pain, truncated only by an untimely death, let us imagine a warm, quiet and wholesome last Christmas in Livonia.

Polmanarkivet is sustained by its Stewards

We have made this article free because we believe our family history belongs to everyone. If you value this work, please consider becoming a Steward of the Archive. Your annual contribution ensures these stories are never lost again.

Become a Steward[[1]]: The claret wine created here in 1467 is still sold. This is Europe's oldest pharmacy. Marzipan was sold at pharmacies for its medicinal properties, but was also a luxurious treat.

[[2]]: “The story of the Christmas tree on Town Hall Square", Visit Tallinn, https://www.visittallinn.ee/eng/visitor/ideas-tips/tips-and-guides/christmas-tree; Juris Kaža and Liis Kängsepp, “Who Decorated the First Christmas Tree? A Battle in the Baltics is Branching Out”, The Wall Street Journal, 23 December 2013, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-SEB-78951

[[3]]: Kazimierz Popławski, “Folk Traditions of Estonia Christmas” (tr. Szczepan Witaszek), 2007, https://www.eesti.pl/folk-traditions-of-estonia-christmas-1371.html; “Christmas Traditions in Estonia", 2013 and 2022, Estonian World, https://estonianworld.com/life/christmas-customs-estonia/

[[4]]: The Livonian War started in 1558.

[[5]]: Theocharis N. Grigoriadis and Alise Vitola, “Shades of Empire: Evidence from Swedish and Polish–Lithuanian Partitions in the Baltics,” The Economic History Review (2025), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ehr.13410.

[[6]]: “Late Medieval Christmas was a German Invention", Medieval Histories, 14 December 2016, https://www.medieval.eu/late-medieval-christmas-german-invention/

[[7]]: Popławski, “Folk Traditions”

[[8]]: Riëtha Kühle, Princess Auguste: On a Tightrope Between Love and Abuse (Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing, 2021), chapter 11

[[9]]: Catherine II to Auguste, quoted in Kühle, chapter 13

[[10]]: Kühle, chapter 12

[[11]]: A 1787 letter, quoted in Kühle, chapter 13

[[12]]: Lebkuchen were spicy gingerbread-like cookies dating back to the 14th century, and Stollen is a dense fruit bread shaped to symbolize the swaddled baby Jesus.