Jürgen Polman d.ä.

Personakt2. Gertrud von Bremen

The Polman Patriarch

Jürgen Polman (The Elder), also known by the names Georg and Göran, was born in the mid- to late 16th century. He was the son of Hans Polman and Margarete, confirmed both through genealogical research and an archival testimony from 1603.[[1]] Hans Polman was a county clerk in Padise (Kloostri), which is a historically significant parish located in St. Mattias in Estonia.

Jürgen’s first wife was Anna Wesell, and he later married Gertrud von Bremen (after 1604). His son Jöran (also known as Jürgen The Younger) was born in 1597. Jürgen had three other sons – Claus, Henrik Johan and Fredrik – as well as a daughter named Katarina (Catharina).[[2]] Sources suggest[[3]] that Claus was the progenitor of the von Pohlmann family line, registered at the Knights’ House in Reval[[4]] (Tallinn) under No. 112.[[5]]

An impressive portrait of Jürgen Polman the Elder by an unknown artist, painted in the first half of the 17th century, is held in the collection of Karlberg Castle in Sweden.[[6]] It depicts the patriarch wearing a somewhat stern expression and generous gold-hued attire with silk and lace trimmings. The family coat-of-arms can be seen on the left; far below it, Jürgen grips a staff with his leather-encased hand in a stance fitting for a commander and patriarch.

Swedish service

Throughout his adult life, Jürgen seems to have aligned with and remained loyal to Swedish monarchs who vied for control of the region. This is evidenced by the various, if sometimes fleeting, properties and parcels of land that he received in return for his service. At least one source[[7]] refers to Jürgen as an Oeconomus Amtmann, implying a financial position for a diocese similar to a bailiff.

Fig. 2 – Left: Unknown Artist, Karl IX (1550–1611), date unknown, oil on canvas (Grh 456). Right: Attributed to Jacob Hoefnagel (1575–1630), Gustavus Adolphus (1594–1632), 1624, oil on canvas. Jürgen Polman's long career was defined by his service to these two monarchs. Image by Nationalmuseum/Gripsholm Castle (PDM).

On 20 November 1600, Jürgen entered the service of Duke Karl of Södermanland. Around this time, in exchange for a sum of money that Jürgen had formerly advanced to the Duke, Jürgen was given the manor Piigandi (Pigant).[[8]] This was a “knight manor” located in the Kannapäh parish of Estonia, owned by Polish families and later seized by them once again.

Duke Karl wrote to him expressing his delight that Jürgen had succeeded in enlisting more than a hundred farmers during the Polish-Swedish War (1600-1611).

The granting of such fiefdoms during this time often involved a commitment to “horse service,” wherein a horse was to be provided by the recipient for the army. Presumably this amounted to enlisting should the need arise, but it’s possible that it was interpreted more freely. In 1601, Jürgen was tattled on by a few noblemen, and was named on a list of Livonian noblemen who did not personally participate in the horse service but sent a servant instead.[[9]] The consequences could involve losing land and privileges.

Jürgen became a captain or hauptman at Anzen (Antsla) in Estonia in 1601.[[10]] Duke Karl wrote to him expressing his delight that Jürgen had succeeded in enlisting more than a hundred farmers during the Polish-Swedish War (1600-1611). The Duke encouraged him to involve even more farmers in their cause by alleviating taxes for those who enlisted, and suggested that Jürgen get in touch with an old warrior, Herman, a driver or förare (a corporal rank), who could lead the peasants.[[11]]

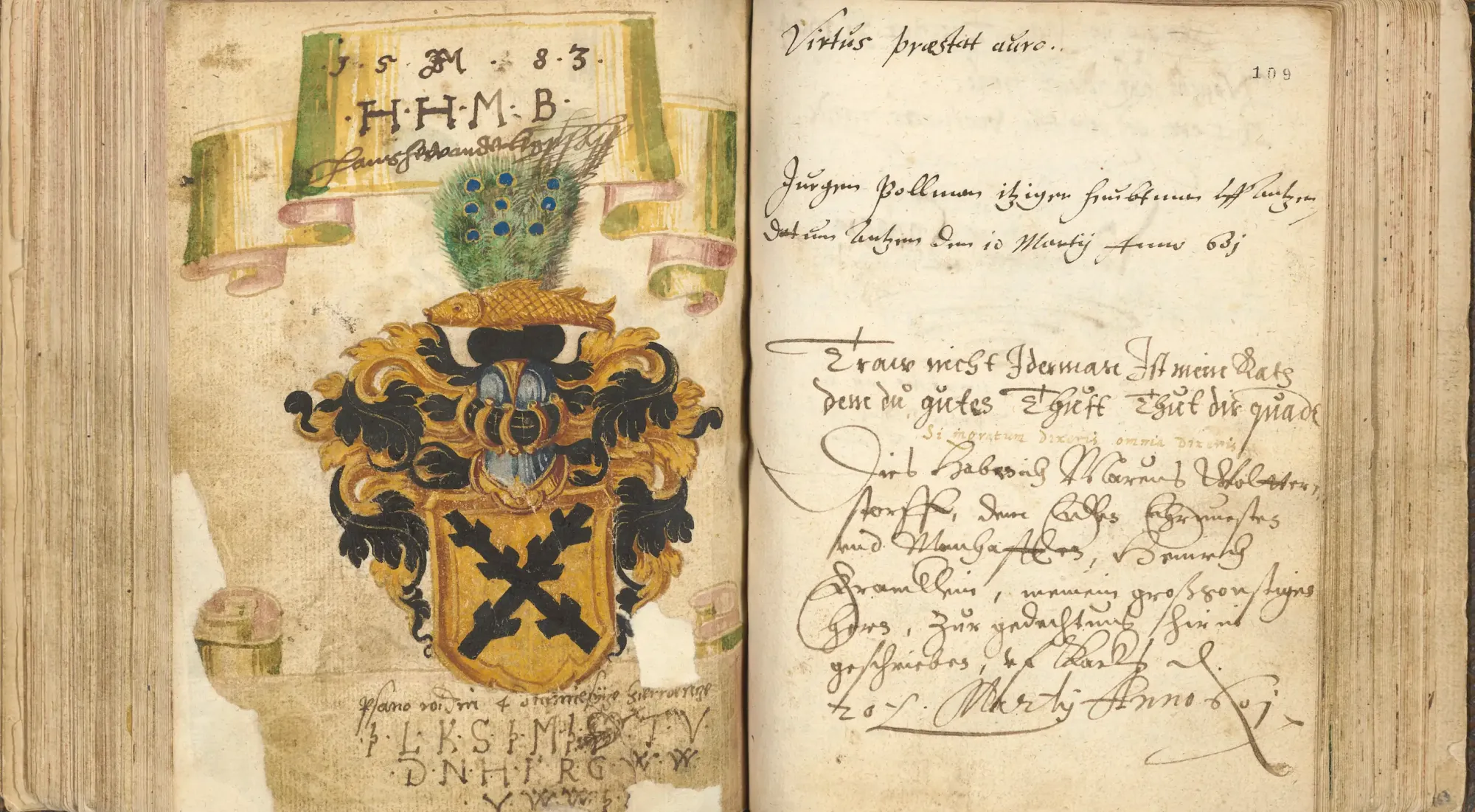

Around the time of his new position, Jürgen crossed paths with Henrik Frankelin, the son of an English nobleman[[12]], who served as the valet de chambre of Duke Karl. He was a traveller who kept a pedigree or friendship book signed by people he encountered. These “signatures” often included coats of arms, mottos, greetings, dates and locations. Jürgen was among those who signed Frankelin’s book, writing: “Jürgen Pollmann, incumbent Captain on Antzen, given on the 10 of March 1601.”[[13]] In 1600-1601, Franklin participated in the duke’s campaign in Livonia, where Jürgen was also in service.

The Polish-Swedish War

Livonia was embroiled in the decade-long war between 1600-1611. Jürgen’s region of Anzen was located near Dorpat, and he may have participated in the Siege of Dorpat in late 1602, as well as the Battle of Rakvere on 5 March 1603 – following which Dorpat surrendered a month later on 15 April. The same month, Livonians were instructed to present themselves in Vyborg on 4 June 1603.[[14]]

...if I, against all hope, should not be freed any time soon, it will cause great loathing among many righteous people who will think twice to risk their life and limb again. - Jürgen Polman

Now in his third year of service, Jürgen was likely captured at some point following this event, possibly in hostile territory en route to Vyborg. He subsequently wrote a letter to his commander, Anders Lennartsson, urging Lennartsson to secure his freedom at the earliest. Lennartsson was the commander of the Swedish forces (together with Arvid Stålarm) in Livonia. Expressing his gratitude to be alive and held in the favour of the commander, Jürgen wrote that he had heard of a plan for his freedom “in exchange for a Polish prisoner, Mikolaj Polikowsky, who has been captured near Patzkloster a little while ago.”[[15]] In the letter, dated 10 August, Jürgen reminded Lennartsson that he had served the Crown of Sweden:

“honestly, veraciously, and faithfully, at my own cost with four horses under the [Dorpat?] banner, and have proven my reliability and faithfulness with my property, limb and blood, in this last foray, and because my wife and children shall not remain inconsolable and must not fall into poverty, therefore I appeal to Your Grace You might agree and make possible that the said Mikolaj Polikowsky will be freed in exchange for me, and the matter will not be drawn out, but that with the next envoy, I may receive an agreeing, solaceful reply, with time and location where the exchange shall take place.”

Jürgen threw in a mild threat for good measure, claiming that “if I, against all hope, should not be freed any time soon, it will cause great loathing among many righteous people who will think twice to risk their life and limb again.” Given his role in recruiting farmers for the war, applauded personally by Duke Karl, this statement is likely to have held weight.

The reward

The following year, in 1604, Duke Karl was officially declared Karl IX, sovereign of Sweden. That same year, according to Werner Tawaststjerna,

“a group of Livonians (Germans) noblemen visited Charles IX asking that they would be granted farms in Finland where their wives and children could be supported because they themselves fought against the enemies of the kingdom. The King agreed to their request and ordered Councilor Arvi Henrikinpoika Horn to be distributed by the chief Tönne Yrjönpoja to the mentioned lords, so that each of them received an income of 150 thalers a year; the Livonians still had to make it a good horse service.”[[16]] Werner Tawaststjerna, 1935

Jürgen, hopefully freed without delay, may have been among this group, or at least benefited from their request. On 2 June 1604, he received from Karl IX a grant of estates in Sääksmäki parish[[17]] in Finland as a reward for his loyal service, which he held for fifteen years.

Since wars were frequent and money tight, these fiefdoms and land grants were awarded instead, many of them in Finland. The requirement for horse (cavalry) service was still strictly upheld. This is illustrated in the case of a Livonian named Philipp Urader, one of Jürgen’s peers, who was unwell and unable to fulfil the conditions, and lost his land as a result.

“… In April 1603 [Urader] received the instruction that every Livonian should present himself with his equipment in Vyborg on June 4th; many of his compatriots, Thomas Bock, Jürgen Polman, Claus Nidder and others spoke to him in May when they went there with 10 horses …”[[18]] Friedrich Bienemann Jr., 1903

This reward would have benefited Jürgen, who was facing some financial difficulties. In May 1604, his mother-in-law, Anna Schopman, wrote of these to her daughter Anna Wesell. She enquired whether Jürgen was "still at Reval", mentioned a bond he had entered with Conradt Tauben, and urged her to ensure that he paid Anna's father back the money he had been loaned.

“He needs it because every day people come and ask him for the money that he guaranteed for him [Jürgen]. So please help to promote the right thing, so that the 400 Taler and also the bond will be sent over.”

However, she trusted Jürgen nonetheless, and requested his help in another matter involving her husband's money loaned to a bride who died eight days after her wedding.

“[The bridegroom] Wilhelm Berkhausen refuses to pay father the money, but is squandering everything [...], but the bride Sonnenschein had sent two boxes from [Narue] to Reval, [...] and in these boxes among other things, is silverware. So that father can get his payment, I ask you, dearest daughter, to go to the court or mayor, or any local appropriate office and ask for the boxes that are to be found at Hermann Reimers‘ house to be taken and put under seal, and that Jürgen in the presence of honest people shall open them and make an inventory of all the things inside, so that I will get my payment of 146 Polish florin and 6 1⁄2 pennies plus all the money I have to pay as fees. Father’s business is my business, and if you do not help here, he will not see a single shilling.”[[19]]

But I want to give credible and sincere testimony about him, that he has behaved as a noble and honest soldier does and should... - Axel Kurck

In 1608, Jürgen’s service was recommended by his superior, Axel Kurck, Chief of the Army of King Karl IX. Kurck wrote a letter to the king, insisting that he wanted to “give credible and sincere testimony about him, that he has behaved as a noble and honest soldier does and should, and has been diligent on guard and as a scout, as well as all other duties and matters that were asked of him at his Royal Majesty’s behalf to perform and to comply.” The note, borne to the king by Jürgen himself, stated that he had requested a “passport and proof”, presumably for which Jürgen required the king’s approval.[[20]]

Manors and property

In 1613, Jürgen was granted the power of attorney to be the ståthållare[[21]], or steward and governor of Padise. He, in turn, answered to Gabriel Bengtsson Oxenstierna, the ståthållare at Refle – an older name for Reval.[[22]] In 1614, he was assured the entire parish of Sääksmäki – only to be asked to give up half of it a year later to Peder Hansson, unless Jürgen was willing to pay off Hansson’s debt.[[23]] In 1615, he was briefly pledged the Estonian knight manor Tuttomäggi (Tuudi) in the parish of Karusen by its heirs – but this too slipped away.

The same year, Jürgen once again had to appeal for fairness with a reiteration of his faithful service, alongside recommendations from his superiors. This time it was in a letter to Axel Oxenstierna – the Lord High Chancellor of Sweden – regarding the unfair redistribution of one of his existing fiefdoms. Granted in 1604 in Nyeköping, the fiefdom had been confirmed as recently as 21 April 1614. Jürgen requested Oxenstierna’s intervention, indignantly stating his case:

“I must remind you that His Majesty on 12 June 1602 in Stockholm assured the poor region of Dorpat – whose inhabitant with others I am – that, should the town Dorpat fall under Polish control, in this unexpected case His Majesty would take care of us poor exiles either in the empire, or in Finland, and that for 150 Talers income, the vassals shall provide a horse for the army, as was ruled on 30 June 1604 in Nieköping. Yet, against all my confidence, longstanding service and fairness, under our Majesty my gracious King on 18 July 1615 the captain of cavalry Peder Hansen acquired 12 of the best farms of my feoff, claiming that I had not provided the horse, as I should have, for a long time, an accusation which is not true as I can prove.”

Jürgen’s plea requested the return of his fiefdoms without the duty to provide horse service, and he promised to step down and renounce said fiefdoms within “four or five years.”

The village of Öetels in Fodials vakka in the parish of Emmern (St. Petri) was given to him in 1623 as a donation from King Gustavus Adolphus, without an expiry date on the fiefdom, confirmed the following year and again in 1631.[[24]] Here, Jürgen built a knight manor called Öötla.

A letter by Alexander von Essen to the King dated 1627 points to further land proprietorship – the villages of Nurmsi and Sargvere in Estonia had been previously leased to Jürgen, but he was obliged to return them by the following year after making use of the farm. The letter was signed and sealed by Jürgen as well as von Essen, who had inherited the villages and wanted them back.[[25]]

Twilight years

Later in his career, Jürgen was promoted to the position of ståthållare (commander), as well as Kirchenvorsteher (church warden or officer) for the Petri parish, where Öötla was located.[[26]] It often fell to the Baltic German nobility in Livonia to contribute to or supervise their local administrative and parish matters, such as ensuring that the manors were maintaining road networks.[[27]] This implies that Jurgen was not necessarily a member of the clergy but required to attend to such matters as part of his position.

In 1628, he was a witness in a border and haystack dispute settlement between the peasants of two villages, Jerwen and Wierlandt, and was present at the inspection of the border.[[28]] As someone with knowledge of the border, his involvement was likely ordered by the governor of Ehesten, Johan De la Gardie – who also appointed Johan von Fietingkhoff as the judge for the case – and is documented via Jürgen's signature and seal attesting the inspection. There were attempts to correct the boundary, seek clarification and handle the matter with sensitivity.[[29]]

When Jürgen died, supposedly between 1632 and 1641, his widow Gertrud was allowed to retain Öötla.[[30]]

[[1]]: Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, Genealogisches Handbuch der baltischen Ritterschaft 1 [Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthood 1] (Görlitz: Verlag für Sippenforschung und Wappenkunde Starke, 1931); The Baltische Familiengeschichtliche Mitteilungen (1934, nr 4) from the original Reval City Archives, 11 October 1603

[[2]]: Born c. 1610, and later married Blasius Semetana.

[[3]]: “Geschlechtsbuch der Familie von Pohlmann”, Rahvusarhiiv (National Archives of Estonia), Immatrikuleeritud Aadli Sugukonnaregistrid Matriklikomisjon, https://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.854.3.284:1, accessed: 4 March 2023

[[4]]: The name Reval was used for seven centuries after the Danish conquest of the city in 1219, until 1918. The region was historically called Livonia, home to the Livonians, comprising parts of present-day Latvia and Estonia.

[[5]]: “Påhlman nr 501”, Adelsvapen-Wiki, https://www.adelsvapen.com/genealogi/Påhlman_nr_501, accessed: 17 March 2022

[[6]]: A replica of the painting is also held in a manor in Sweden.

[[7]]: Jahrbuch für Genealogie, Heraldik und Sphragistik (Mitau: J. F. Steffenhagen u. Sohn, 1897-88), 82-86 https://hdl.handle.net/10062/23187

[[8]]: Hagemeister Heinrich von. 1837. Materialien Zu Einer Geschichte Der Landgüter Livlands 2 [Der Dörptsche Kreis]. Riga: Frantz.

[[9]]: Frantzen’s Buchh ed.,”Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Alterthumskunde der russischen Ostsee-Provinzen”, Mittheilungen aus dem Gebiete der Geschichte Liv-, Ehst- und Kurland’s [Communications from the area of the history of Liv, Ehst and Kurland]. Bd.17, H.1-3 (Riga; Leipzig, 1900), 573-74

[[10]]: “Påhlman, släkt”, Riksarkivet, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/sbl/Presentation.aspx?id=7430, accessed: 21 March 2022

[[11]]: Jakob Koit, “Estnische Bauern als Krieger während der Kämpfe in Livland 1558-1611”, Eesti Teadusliku Seltsi Rootsis aastaraamat = Annales Societatis Litterarum Estonicae in Svecia, no. 4 (January 1966): 39-40, https://dea.digar.ee/article/JVeestirootsiselts/1966/01/0/6

[[12]]: Rowland Frankelin and Dorotea Patavin, presumably a Polish titled princess.

[[13]]: Henrik Frankelin, Henrik Frankelins Stammbuch, 1582-1610 (Uppsala), Y 52, http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:alvin:portal:record-104069 The book now resides at Uppsala University Library and the digitised collection on Alvin.

[[14]]: Friedrich Bienemann Jr., ed. Baltic Monthly, LV (1903): 72

[[15]]: Jürgen Polman, “Letter to Anders Lennartsson”, War History Collection [Krigshistoriska Samlingen], August 10, 1603, SE/RA/754/2/VI/2, Stockholm/Täby, Riksarkivet, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/arkiv/TDahozQEzX3eki5uQwE055

[[16]]: Werner Tawaststjerna, Kaarle IX:n Ja Sigismundin Taistelu Viron ja Liivinmaan Omistamisesta [Charles IX and Sigismund’s Battle for the Ownership of Estonia and Livonia] (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Kirjapainon Oy., 1935), 248

[[17]]: Specifically the quarters of Liettula and Ridvala.

[[18]]: Friedrich Bienemann Jr., ed. Baltic Monthly, LV (1903): 72

[[19]]: Anna Schopman to Anna Wesell, 8 May 1604, translation from German by Beyond History, commissioned by Polmanarkivet in June 2025.

[[20]]: Jören Poolman (Jürgen Polman), “Letter to Axel Korck, Öötla Mõis Kirjakogu [Letter Collection of Öötla Manor]”, February 16, 1608. AM.301.1.1, Ajaloomuuseum, Tallinn https://ais.ra.ee/en/description-unit/view?id=126000012071

[[21]]: In Sweden, the term "ståthållare" has existed since the late Middle Ages, as a title for commanders of fortresses or castles (as with Polman), and part of state administration during the 16th and early 17th centuries (as with Oxenstierna).

[[22]]: Jonas Hallenberg, Svea Rikes Historia Under Konung Gustaf Adolf Den Stores Regering [The History of the Kingdom of Sweden Under the Reign of King Gustaf Adolf the Great] (Stockholm: Carlbohm, 1793) 67

[[23]]: Half the estate including Liettula and Ridvala went to Hansson, while Jürgen kept Salo and Konho until 1619 when they were recalled. Source: Riksarkivet (Contributor), Meddelanden från Svenska riksarkivet: Ny följd II [Announcements from the Swedish National Archives: New consequence II], Volume 6, Issue 3 (Täby: Riksarkivet, 1922), 479 and Gotthard von Hansen, Die Sammlungen inländischer Alterthümer und anderer auf die baltischen Provinzen bezüglichen Gegenstände des Estländischen Provinzial-Museums [Collections of domestic antiquities and other objects related to the Baltic provinces of the Estonian Provincial Museum] (Reval: Lindfors, 1875), 77

[[24]]: Riksarkivet (Contributor), Meddelanden från Svenska riksarkivet: Ny följd II [Announcements from the Swedish National Archives: New Consequence II], Volume 6, Issue 3 (Täby: Riksarkivet, 1922), 640

[[25]]: Alexander von Essen to King Gustavus Adolphus, 27 May 1627, National Archives of Estonia, “Georg Pohlmann’s Verpflichtung gegen Alexander von Essen wegen der Dörfer Nurmis und Sargefer”, no. 1152, https://ais.ra.ee/en/description-unit/view?id=200000395234, accessed: 17 May 2023

[[26]]: “The German parishes and their land ownership in the parishes of Jerwen according to the preachers’ reports on the Pudbeck parish visitation in 1627.” Franz Kluge, Estländischen Literarischen Gesellschaft ed., Beiträge Zur Kunde Ehst-, Liv- Und Kurlands (1902), Band 6, Heft 2 u. 3. Vol. 6, http://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/940967

[[27]]: Bruno Martuzāns, “Before Newspapers and the Telegraph: Information Distribution in Livland More than Two Hundred Years Ago”, Library & Information History 36, no. 2 (August 2020), 116–34. https://doi.org/10.3366/lih.2020.0020.

[[28]]: His name appears as “Georg Pollman”, among a list of landjunkers.

[[29]]: Pabst Eduard. 1861. Est- Und Livländische Brieflade: Eine Sammlung Von Urkunden Zur Adels- Und Gütergeschichte Est- Und Livlands in Uebersetzungen Und Auszügen [Estonian and Livonian letter box: a collection of documents on the history of nobility and goods in Estonia and Livonia in translations and excerpts]. Abt. 2 Schwedische Und Polnische Zeit Bd. 1 Die Jahre 1561 Bis 1650. Reval: Kluge u. Ströhm.

[[30]]: Gustaf Elgenstierna, ed., Den Introducerade Svenska Adelns Attartavlor med Tillagg och Rattelser [The Genealogies of the Introduced Swedish Nobility] (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1925-36) quotes ““Lived in 1632, but was dead in 1641.”