Jürgen Polman the Elder

As the progenitor of the Swedish and Estonian branches, Jürgen Polman[[1]] plays a prominent role in the family's history. Born in the mid- to late 16th century, Jürgen was the son of Hans Polman and Margarete.[[2]] Throughout his adult life, Jürgen seems to have aligned with and remained loyal to Swedish monarchs who vied for control of the region. In 1600, he entered the service of Duke Karl of Södermanland. Jürgen became his captain or hauptman at Anzen (Antsla) in Estonia in 1601.[[3]] Duke Karl wrote to him expressing his delight that Jürgen had succeeded in enlisting more than a hundred farmers during the Polish-Swedish War (1600-1611).

Jürgen’s region of Anzen was located near Dorpat, and he may have participated in the Siege of Dorpat in late 1602 and the Battle of Rakvere on 5 March 1603 – following which Dorpat surrendered a month later on 15 April. Now in his third year of service, Jürgen was captured following the siege and imprisoned. He wrote a letter to his commander, Anders Lennartsson, urging him to secure his freedom at the earliest.[[4]] His plea for freedom was successful, and in 1604 Jürgen received a grant of estates in Sääksmäki parish[[5]] in Finland from Karl IX as a reward for his loyal service, which he held for fifteen years.

In 1613, Jürgen was granted the power of attorney to be the steward and commander of Padise.[[6]] He was assured the entire parish of Sääksmäki in 1614 – only to be asked to give up half of it a year later to Peder Hansson, unless Jürgen was willing to pay off Hansson’s debt.[[7]] In 1615, he was briefly pledged the Estonian knight manor Tuttomäggi (Tuudi) in the parish of Karusen by its heirs – but this too slipped away.

Finally, in 1631, Jürgen received the estate and manor of Öötla (Oethel) in Estonia’s St. Petri parish as a donation from King Gustavus Adolphus. Later in his career, Jürgen was promoted to the position of ståthållare (commander), as well as Kirchenvorsteher (church warden or officer) for the Petri parish, where Öötla was located.[[8]] When Jürgen died, supposedly between 1632 and 1641, his widow Gertrud was allowed to retain Öötla.[[9]]

You can read Jürgen’s full biography at Polmanarkivet here:

Uncovering the Portrait

One week ago, on a rainy Sunday — a perfect day for research — I stumbled upon an intriguing line in the book Castles and Manor Houses in Sweden (Swedish: Slott och herresäten i Sverige).[[10]] Describing a particular manor, it noted:

Mitt emot, över den öppna spisen av italiensk marmor, hänger ett porträtt av Jurgen Polman (död omkring 1640), ättens stamfader. Tavlan är malad efter originalet pa Karlbergs slott. Slott och herresäten i Sverige

It mentioned a portrait of Jürgen Polman, the patriarch of the Påhlman family, hanging proudly above an exquisite Italian marble fireplace. The painting, a replica of the original at Karlberg Palace, dated back to the 17th century, probably around the time of Jürgen’s death.

At first, there was a wave of excitement, but doubts soon swept in. Could there have been a mix-up? Perhaps the author intended to write about Jürgen’s son, Jöran Polman the Younger, whose well-known portrait can be found among Wrangel’s officers in the halls of Skokloster Castle. Yet, upon closer examination, I realized the author didn’t make a mistake. Jürgen Polman was specifically mentioned as the progenitor of the family, with an accurate date of death. As I delved further into the text, I discovered an intriguing detail. There was another reference to the same painting, with the words “den äldre” (The Elder) appended to his name. I jumped out of my seat, but then sat back down with uncertainty. How on earth would I ever locate this elusive portrait?

"We can not find anything when we research the name Jürgen Polman, or a photo of the portrait you are looking for."

Desperate for answers, I reached out to Anna Catellani of Atelje’ Catellani, the chief conservator at Karlberg Palace, who had restored numerous artworks there over the years. Karlberg Palace holds a large number of portraits of royalty, commanders and events which had decisive importance for Sweden. Most of the artwork consist of older paintings on canvas and panels made during the 17th century.”[[11]] However, even her extensive knowledge couldn’t help me find a trace of the portrait in their archives. Catellani suggested I turn to the portrait archive at the Swedish National Archives (Swedish: Riksarkivet), Solna City Image Archive (Swedish: Solna stads bildarkiv), and the Swedish Potrait Archive (Swedish: Svenskt Portrattarkiv) for assistance. Each institution referred me to another, having no idea of its whereabouts:

“Unfortunately we do not have a photograph of Jürgen Polman the Elder in our image archive pertaining to Solna stad.”

“Unfortunately I have no immediate answer to give you, we have to look in to this and get back to you! I’ll let you know as soon as I have more info on the paintings whereabouts.”

“We can not find anything when we research the name Jürgen Polman, or a photo of the portrait you are looking for.”

“Unfortunately I have no idea.”

“Concerning your question about a portrait and photo of Jürgen Polman I can tell you following. There are no photos of him in The Royal Palace archives.”

With hope for the original quickly fading, I turned my attention to the copy mentioned in historical texts. A landmark 1960s book on Swedish manors had documented the portrait’s location at a specific estate, but its current whereabouts were a mystery. After a period of further research, I was able to make contact with the current owner. Soon after, I received a response with words I won’t forget: I do have the portrait you are looking for. This is a researcher’s dream scenario! The owner graciously provided a photo of the copied painting, confirmed its provenance, and permission to include in our archive. Today, the portrait remains in a private collection in Sweden.[[12]]

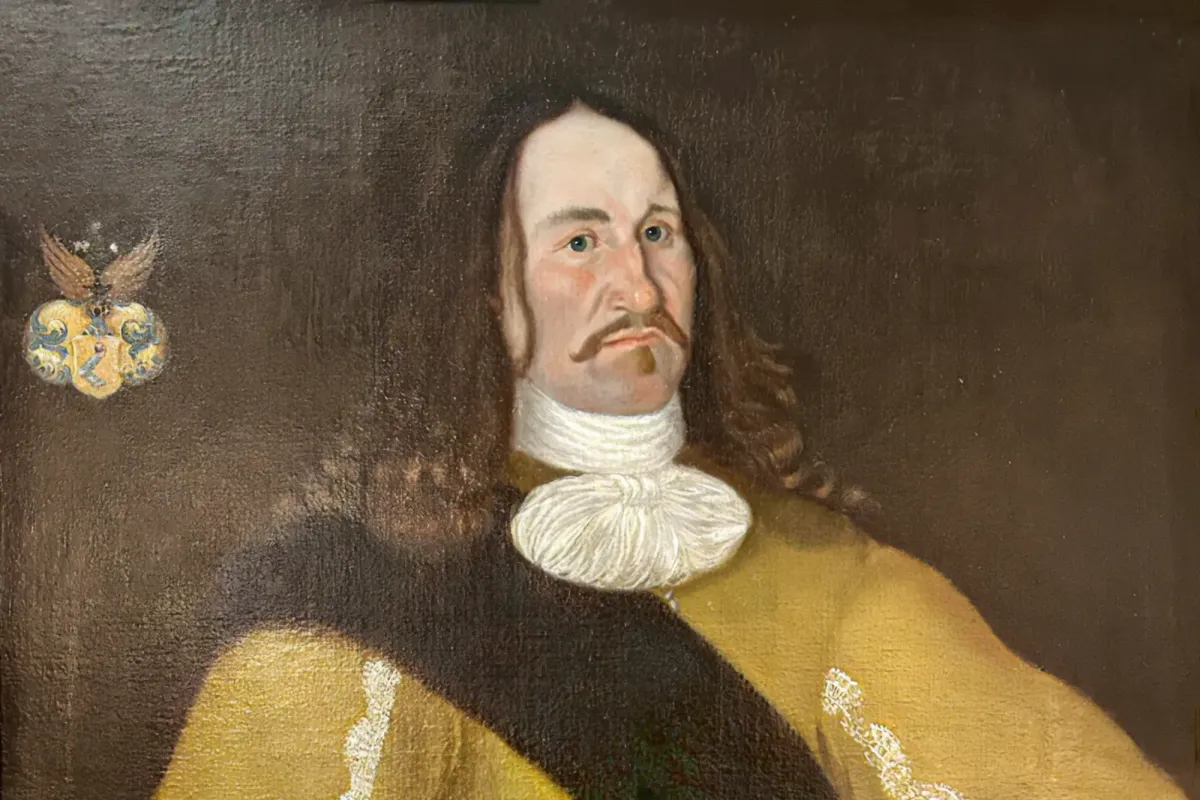

Fig. 2 and 3 - Göran Pålman the Elder (ca. 1576-1641), undated, oil on canvas. Image by Militärhögskolan Karlberg/Polmanarkivet (CC BY 4.0). Left: original painting ca. 1630s located at Karlberg Palace. Right: copied painting ca. 18th century located in a private residence. Image courtesy of the owner.

Soon after, Military Academy Karlberg (Swedish: Militärhögskolan Karlberg) replied to my enquiry about the original painting. They located the original painting, which is in fact located at Karlberg Palace. Jürgen has several aliases, and he is listed in their art database with the name Göran Pålman.

“The age of long locks, lace and leather.”

Portrait of a Patriarch

The portrait depicts a stern-looking Jürgen almost in full-figure, gazing slightly to his left. He has long brown locks and a moustache; for men, the 17th century was an age of leather, long locks and lace,[[13]] as we see here. The family coat-of-arms – an armoured arm holding a bullet – can be seen on the left; far below it, Jürgen grips a staff with his leather-encased hand in a stance fitting for a commander and patriarch. The somewhat tight and rigid posture conveys a sense of pride and control. Jürgen is dressed in a magnificent buff coat, rendered with a golden sheen that mimics opulent fabric. The heavy leather is richly decorated with rows of intricate metallic braid. A black baldric drapes across his body, with a sword hanging on his left side and a wide-brimmed black hat with gold trim in his hand.

The painter of Jürgen’s portrait is unknown. Karlberg Palace maintains a collection of portraits of fältherrar or field commanders. Most of the portraits of field commanders there were painted during the 17th century.[[14]] Many of them are painted by David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl, so it’s possible this is the same artist.[[15]] How these paintings – particularly those of Baltic-German military men in Livonia – became associated with Karlberg Palace is unclear. Many Livonian noblemen served the Crown during the Polish-Swedish War. Jürgen himself went into the service of Duke Karl in 1600. It's possible these paintings came to Karlberg Palace due to their connection to King Karl.

Based on the man's presumed age in the painting, Jürgen's portrait must have been painted in the 1630s. However, the long hair and neckwear and cuffs in the portrait raise questions about this date. He is shown with long locks and wearing a silk cravat wrapped around his neck and tied in a knot, styles that became more fashionable in the late 1640s and 1650s. To resolve these inconsistencies – and to date the painting – we must turn to fashion for further clues.

Don’t want to miss the next chapter?

Become a Member of Polmanarkivet for free to get new research and stories delivered directly to your inbox the moment it's published.

Clues in the Clothes

The trend of longer hair, influenced by the English, was emerging by at least 1629 and was newly fashionable for young courtiers.[[16]] Long curls were de rigueu by the late 1630s.[[17]] Men were even known to wear their hair longer on the left side.[[18]] The long hair by this time is attested in many paintings of the time, including James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton and King Charles I. That Jürgen himself sports longer locks in his portrait is not unusual given artworks of the era.

Fig. 5 - Daniel Mytens (1590-1647), James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton, 1629, oil on canvas. Image by National Galleries Scotland (CC BY 4.0). Fig. 6 - Daniel Mytens (1590-1647), King Charles I, 1631, oil on canvas. Image by National Portrait Gallery (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

The issue of the cravat is more difficult to tie down. In the 1640 portrait Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer,[[19]] a lace collar is notably gathered into a bow at the front of the neck—a precursor to the cravat, which would eventually replace the large lace collars prevalent in the early seventeenth century. The Swede Emanuel De Geer's portrait from 1656 depicts a knotted scarf at his neck.[[20]] This type of cravat became more popular in the middle of the century and by the 1670s, it had become the dominant neckwear style, supplanting the lace collar.[[21]]

There are many attestations of this in paintings from the era:

Fig. 7 - Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck (1606/1609-1662), Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer, 1640, oil on canvas. Image by National Gallery of Art; Fig. 8 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613-1670), Emanuel De Geer, 1624-1692, 1656, oil on canvas. Image by Nationalmuseum; Fig. 9 - John Michael Wright (1617-94), Sir William Bruce, c 1630 - 1710. Architect, ca. 1664, oil on canvas. Image by National Galleries Scotland; Fig. 10 - Augustine Briggs (1617-1684), Mayor of Norwich, 1670, oil on canvas. Image by Norwich Castle Museum.

In Jürgen's portrait, his silk cravat is an enigma, prompting questions about the era in which it was painted. While popular artwork of the time tell part of the story, we need to turn to the history of the cravat for more nuanced understanding.

The birth of the cravat is thought to have emerged during the Thirty Years' War when Croatian cavalry units came into contact with the Imperial Army of the Holy Roman Empire. Coming into contact with French soldiers, the unique neckwear style of the Croatians caught their attention. Croatian soldiers later served in France from 1635 onwards, and in 1667, a special regiment called the Royal Cravates was formed.[[22]]

While common soldiers wore scarves made of coarse materials, officers opted for fine cotton or silk scarves. After the French, the Belgians and the Dutch also embraced the cravat, it eventually spread to the British Isles, rapidly gaining popularity across Europe. At the earliest, we see an early cravat in the 1622 portrait Ivan Gundulić, the prominent Baroque poet.[[23]] According to Dubrovnik legend, this painting is the first instance of a man wearing a cravat.

It's not out of the question that officers in Sweden and Livonia came into contact with the cravat style during the Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War between 1630 and 1635. Even so, there are examples of the cravat during this period even if they are rudimentary.

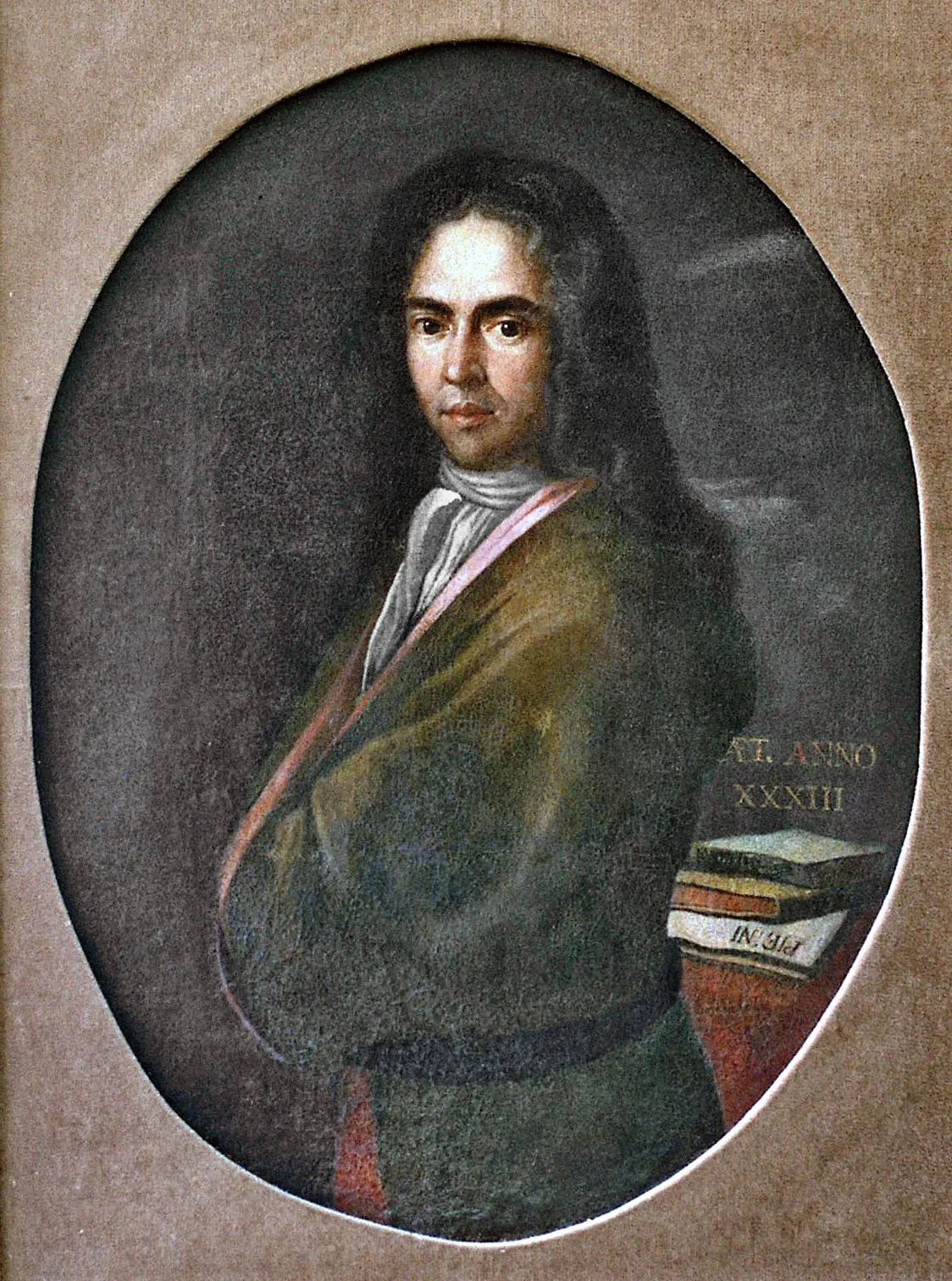

Perhaps the most compelling evidence is the copied portrait of Johan Reuter af Skälboö (1585 - 1644), a Swedish nobleman who lived during Jürgen Polman’s time. The painting shows an identical uniform – gold fabric, silk collar, lace trimmings, and a black sash. The striking similarity between the two portraits suggests that they were likely painted around the same time by the same artist. With Jürgen's death circa 1641 and Johan's death in 1644, the evidence suggests the portraits were completed in the late 1630s or early 1640s.

Born in 1585, Johan participated in the Battle of Kircholm in 1605, after which he was promoted to lieutenant and received horses and clothing with all accessories from King Carl IX. During the siege of Riga in 1621, he risked his life by crossing the Dünaström, an ice-covered river, and unexpectedly had a bridge built over it to the king’s great pleasure. He was shot during the siege with a musket ball that passed through his mouth and out through his cheekbone.[[24]]

In 1634, he was appointed county governor of Älvsborg County. He also served as the commandant of Gothenburg from 1634, until his death in 1644. In his final days, he served as the commandant in Birzen while recovering from an illness. As a desperate measure, he placed gunpowder around his bed, intending to blow himself up rather than surrender the city to the enemy. His final words expressed his unwavering loyalty to Gothenburg, stating that he would rather fall in his shoes than he would ever give up the city.

Johan was buried in Levene Church on January 25, 1644, where his grave and that of his descendants can be seen.

A Mystery Remains

After reviewing all the evidence, there are three possible interpretations of the portrait: it might depict Jürgen Polman as an example of an emerging fashion trend; it could represent Jürgen, painted posthumously in the style of the time; or it may portray Jürgen, suggesting he lived later than previously thought, around the late 1640s. There’s also a less likely possibility that the portrait features one of his descendants, like his grandson Johan Polman, who was knighted Johan Påhlman in 1650 and became a ryttmästare in 1659.

Neither Jürgen Polman nor Johan Reuter look like advant garde men, so it's unlikely that the portraits were painted while they were still alive wearing uniforms that were not yet in fashion. The most likely scenario is that they were done posthumously, and since there weren't any records of how the men actually dressed, the artists just painted them in clothes of the time.[[25]] It’s unclear whether this practice was common in seventeenth-century portraiture. If that were the case, it could potentially date the painting to the middle of that century. Regardless, it's a fascinating bit of history.

We may never know the full story of Jürgen the Elder's portrait. As researchers, we must accept some uncertainty at times. A touch of mystery keeps us going!

Locating Portraits: Tips for Genealogists and Family Historians

If I’ve learned anything from this experience, it’s to have patience. I’d like to end this post with three tips for genealogists and family historians who are trying to locate portraits of their ancestors.

Don’t give up. It’s easy to become frustrated, especially when you know an artwork exists and you can’t locate it. Be persistent because you don’t know what you’ll find along the way. Even if you don’t find the exact painting or artefact you’re looking for, you might come across something else that’s valuable in your research. In this case, in the effort to locate the painting of Jürgen, I also found other interesting tidbits related to his heirs. With that in mind, leave no stone unturned (even if the stone feels irrelevant in the moment).

Don’t be afraid to ask for help. We cannot hope to do this research alone. Odds are someone has researched the same ancestor or branch of the family, or they can point you in the right direction. I communicated with nearly 10 different people in trying to locate this painting and it paid off. Even if they didn’t know of the painting or its whereabouts, they provided me with other suggestions. If your ancestor is from Sweden in particular, you’re in luck! I’ve found Swedes to be among the most helpful in trying to help you with your research.

Don’t search in only the obvious places. Google is not always your friend here (although it can be helpful). You’ll need to visit or contact local museums, archives, or specialists to help you. It’s even better if you know the exact parish or municipality your ancestor came from, or where your evidence tells you the painting is located. Also, don’t limit your search to obvious places like the national archives (for example, Riksarkivet in Sweden). In Sweden, much of the nation’s rich heritage is found in historic houses, stately homes, landed estates and regal residences — these manor houses were once owned by noble families and many of them are still privately owned. Ask nicely — and respect privacy — and you might find they are happy to help.

Polmanarkivet is sustained by its Stewards

We have made this article free because we believe our family history belongs to everyone. If you value this work, please consider becoming a Steward of the Archive. Your annual contribution ensures these stories are never lost again.

Become a Steward[[1]]: also known as Göran, Jöran and Georg Polman/Pohlman/Pålman

[[2]]: Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, Genealogisches Handbuch der baltischen Ritterschaft 1 [Genealogical Handbook of the Baltic Knighthood 1] (Görlitz: Verlag für Sippenforschung und Wappenkunde Starke, 1931); The Baltische Familiengeschichtliche Mitteilungen (1934, nr 4) from the original Reval City Archives, 11 October 1603

[[3]]: “Påhlman, släkt”, Riksarkivet, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/sbl/Presentation.aspx?id=7430, accessed: 21 March 2022

[[4]]: Jürgen Polman, “Letter to Anders Lennartsson”, War History Collection [Krigshistoriska Samlingen], August 10, 1603, SE/RA/754/2/VI/2, Stockholm/Täby, Riksarkivet, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/arkiv/TDahozQEzX3eki5uQwE055

[[5]]: Specifically the quarters of Liettula and Ridvala.

[[6]]: Jonas Hallenberg, Svea Rikes Historia Under Konung Gustaf Adolf Den Stores Regering [The History of the Kingdom of Sweden Under the Reign of King Gustaf Adolf the Great] (Stockholm: Carlbohm, 1793) 67

[[7]]: Half the estate including Liettula and Ridvala went to Hansson, while Jürgen kept Salo and Konho until 1619 when they were recalled. Source: Riksarkivet (Contributor), Meddelanden från Svenska riksarkivet: Ny följd II [Announcements from the Swedish National Archives: New consequence II], Volume 6, Issue 3 (Täby: Riksarkivet, 1922), 479 and Gotthard von Hansen, Die Sammlungen inländischer Alterthümer und anderer auf die baltischen Provinzen bezüglichen Gegenstände des Estländischen Provinzial-Museums [Collections of domestic antiquities and other objects related to the Baltic provinces of the Estonian Provincial Museum] (Reval: Lindfors, 1875), 77

[[8]]: “The German parishes and their land ownership in the parishes of Jerwen according to the preachers’ reports on the Pudbeck parish visitation in 1627.” Franz Kluge, Estländischen Literarischen Gesellschaft ed., Beiträge Zur Kunde Ehst-, Liv- Und Kurlands (1902), Band 6, Heft 2 u. 3. Vol. 6, http://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/edition/940967

[[9]]: Gustaf Elgenstierna, ed., Den Introducerade Svenska Adelns Attartavlor med Tillagg och Rattelser [The Genealogies of the Introduced Swedish Nobility] (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1925-36) quotes ““Lived in 1632, but was dead in 1641.”

[[10]]: This seminal work is regarded as the most comprehensive historical art reference on Swedish manor houses, royal palaces, and state-owned castles.

[[11]]: Karlbergs Slott”, Ateljé Catellani, https://ateljecatellani.se/karlbergs-slott-2/, accessed: 21 August 2023

[[12]]: To the donor, I humbly thank you!

[[13]]: “1630-1639”, Fashion History Timeline, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1630-1639/, accessed: 31 August 2023

[[14]]: Karlbergs Slott”, Ateljé Catellani, https://ateljecatellani.se/karlbergs-slott-2/, accessed: 21 August 2023

[[15]]: It’s believed that all of these portraits have been conserved and restored, so either this portrait was missing or part of a different collection.

[[16]]: De Young, Justine. 2018. “1620-1629 | Fashion History Timeline.” Fashion History Timeline. State University of New York. 2018. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1620-1629/

[[17]]: Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. “1600–1650 in Western Fashion.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. December 12, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1600%E2%80%931650_in_Western_fashion

[[18]]: De Young, Justine. 2018. “1630-1639 | Fashion History Timeline.” Fashion History Timeline. State University of New York. 2018. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1630-1639/

[[19]]: De Young, Justine. 2018. “1640-1649 | Fashion History Timeline.” Fashion History Timeline. State University of New York. 2018. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1640-1649/

[[20]]: De Young, Justine. 2018. “1650-1659 | Fashion History Timeline.” Fashion History Timeline. State University of New York. 2018. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1650-1659/

[[21]]: De Young, Justine. 2018. “1670-1679 | Fashion History Timeline.” Fashion History Timeline. State University of New York. 2018. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1670-1679/

[[22]]: “Cravat in History.” 2017. Academia Cravatica. February 14, 2017. https://academia-cravatica.hr/cravat-in-history/

[[23]]: “Ivan Gundulić.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. October 26, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Gunduli%C4%87

[[24]]: “Reuter Af Skälboö Nr 158 - Adelsvapen-Wiki.” 2023. Adelsvapen.com. 2023. https://www.adelsvapen.com/genealogi/Reuter_af_Sk%C3%A4lbo%C3%B6_nr_158

[[25]]: De Young, Justine. Email to Jake Peterson. Fashion Mystery in 17th Century Portrait, November 1, 2024.