I read Arcadia on the train from Oslo. My parents and brother are around me; an ever-refilling trolley of snacks and candy within arm's length; quaint Norwegian farms and landscapes and a gigantic rainbow flash by the window. I think of Peter Cederström, journeying alone on a ship from Sweden in search of better opportunities in this neighbouring country. It is nearly three years since we wrote about him, and nearly two centuries since the young Swedish hatmaker[[1]] first arrived in the city I'm headed towards.

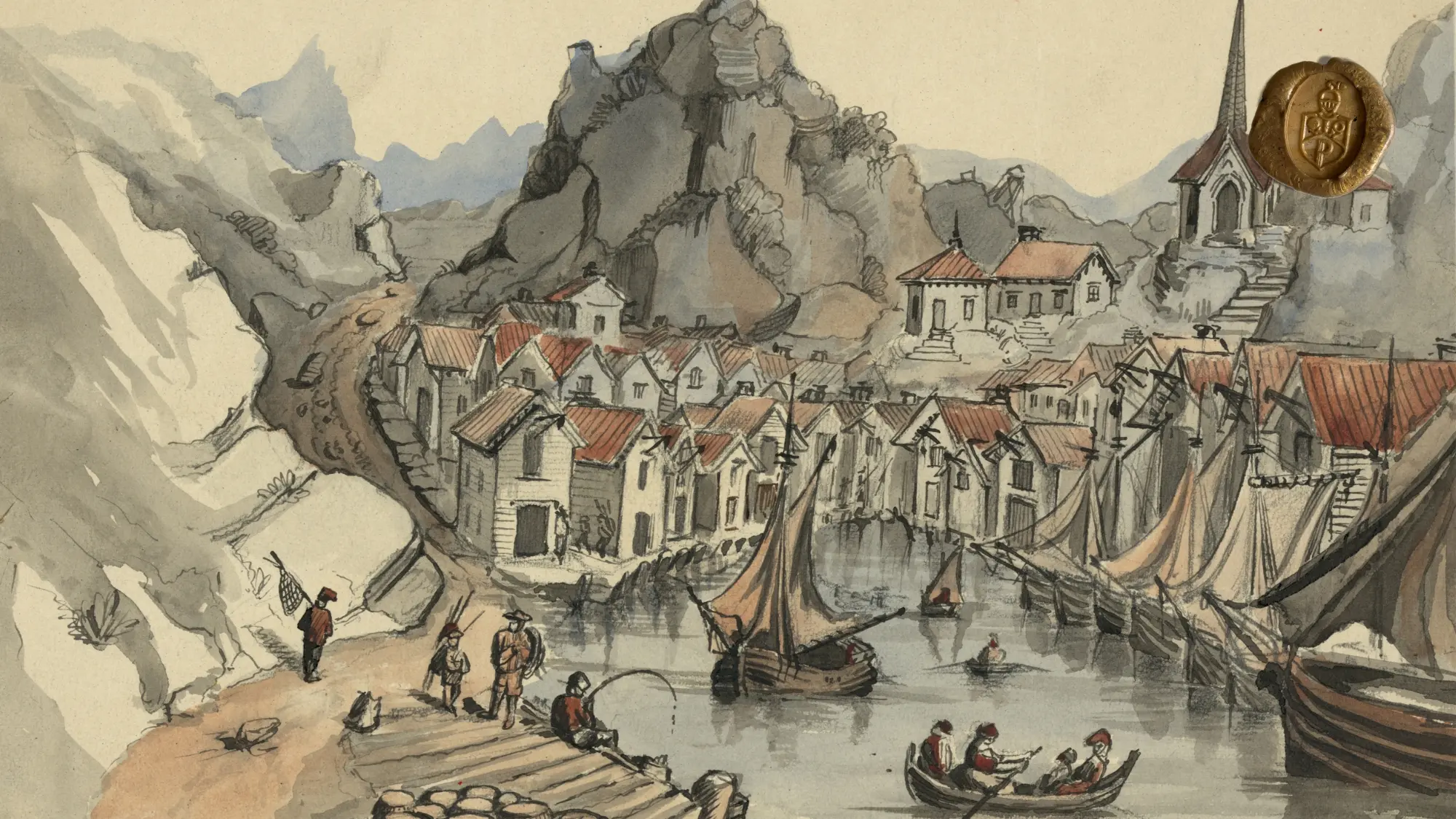

I'm greeted by a view of sloping red roofs from the hotel window. Rows of white timber houses are the highlight of the quaint, hilly cobblestone lanes. Given that many of them – especially in Gamle Stavanger or the Old Town – are restored and date back to the 18th and early 19th centuries, Peter may have been confronted by a similar scene when he landed.[[2]] The homes in the historic city centre, now mostly privately owned, show off their heritage status with vines, perfect hedges and flower baskets adorning windowsills. Elsewhere, on some streets, they are juxtaposed with contemporary street art and murals that nearly always make me pause.

In 1830, Peter married his bride Tobia Thorsdatter Hommeland, the daughter of a yacht skipper from Rogaland, at this church; somehow the bells feel auspicious as we listen nearby.

The next morning, the lanes lead me to the main city centre. A statue of renowned author Alexander Kielland (1849-1906)[[3]] stands on a plinth facing the water, surrounded by restaurants and modern businesses, with a very real seagull almost always perched on his top hat. Being in Stavanger means never being far from water; five lakes and three fjords compete for attention. In the early evening, we walk along the breezy harbour where a few ships are docked, fringed by charming buildings on both sides. Tollboden, the 1905 customs house that was the hub for all the cargo coming into and leaving the port, still stands in its ochre and maroon glory.[[4]] A red telephone booth converted into a library, one of 100 remaining boxes in the country,[[5]] proclaims,

“Even if the ring tone is gone, our telephone boxes have important stories to tell. Stories of a time when you couldn't carry your phone around in your pocket. Stories about us.”

The domkirke, or Stavanger Cathedral, is closed for renovation. Located directly behind Kielland's statue, it is the oldest cathedral in Norway, and took half a century to complete (ca. 1100-1150). In fact, the building of the cathedral coincided with the founding of Stavanger as a city in 1125. I circle it, staring up at the grey stone. The beautiful Breiavatnet lake – situated between two fjords – stretches in front of it, replete with a fountain, foliage, statues, seagulls and swans. A notice announces a carillon performance[[6]] that evening at six, with an array of compositions. In 1830, Peter married his bride Tobia Thorsdatter Hommeland, the daughter of a yacht skipper from Rogaland, at this church; somehow the bells feel auspicious as we listen nearby.

Stavanger became a municipality in 1838, and in the second half of the 19th century, absorbed many smaller surrounding regions. Over the following decade, the district of Storhaug became its “industrial centre of gravity”. It was here, in this very borough[[7]], that the Cederstrøms started their family of nine children between 1831 and 1850. Their home during this time[[8]] was located on Gaden til Østervåg, now known as Steinkargata. I accidentally spot a sign for the street as it leads us to a Mexican restaurant for dinner. But a cursory look does not reveal number 11[[9]], even though I'm standing right about where it ought to be.

Fig. 3 Steinkargata in Stavanger in 2024. Image © Kriti Bajaj; Fig. 4 Steinkargata in Stavanger c. early 20th century. Image by Stavanger byarkiv.

I approach Steinkargata from a different street the next day, but number 11 is still elusive. I find the neighbouring numbers, and walk up and down the street a million times. Eventually, I conclude that it might be 1) hidden behind another house that I don't have access to; 2) was destroyed in a fire or during the city's modernisation; or 3) the address changed but the house still stands. Later, I visit the Sølvberget Library to see if they can offer any information, but have no luck. (They recommend checking out Stavangerbyarkiv.no or the history section, but warn that the books would likely all be in Norwegian).

Though Stavanger was growing rapidly in the mid-19th century, its infrastructure was hardly equipped to handle such changes.

There is no organised sanitation, water, or sewage system, and people live in close quarters. The city reeks. The overcrowded immigrant quarters in the eastern part of the city, where epidemics like measles spread rapidly, are marked by high infant mortality. More than half of the funerals in the city are children's funerals. Although a few in the city become wealthy from herring and shipping, the vast majority have to work hard for little money. In Blåsenborg, it is not uncommon for 20-25 people to live in one house.[[10]]

Fires were also common enough to warrant night patrols and the building of a watchtower in the early 1850s. Wandering up Valberget, the Valbergtårnet (Valberg tower) proclaims 1852 as the year of its inception. With its green door and green turret, it is a small museum with a view of the city's skyline. Directly opposite it is a mural of smoke, perhaps a commemoration of the fire of 1860, which the watch was unfortunately unable to prevent. Over 200 houses were destroyed in the fire, including some in Østervåg.

I find myself slightly emotional imagining the Cederstrøms a couple of centuries ago entering and exiting those doors, and living and working behind them.

The same year, Peter married Ragnhild Svendsdatter (his first wife, Tobia, had passed away in 1853). His next address, as recorded in the 1865 census, is much easier to locate. Bakkegata 18, formerly 159 Bakkens Rode, is a prime spot in contemporary Stavanger, also located in Storhaug, running perpendicular to Steinkargata. Flanked by two trendy bars, it's true that the building adjoining it is getting far more attention for its vibrant exterior, but I'm excitedly photographing number 18 from all angles.

It still looks almost exactly like the photograph we have from the Stavanger City Archives, albeit with new window trimmings. I find myself slightly emotional imagining the Cederstrøms a couple of centuries ago entering and exiting those doors, and living and working behind them. I get several curious looks as people watch me aim my camera and then look at the house for themselves, not comprehending what I find so intriguing about it. A tourist engages me in conversation and I excitedly share the story.

Bakkegata exits onto Fargegatan, a happening street lined with popular bars and restaurants, painted in a myriad colours, and wearing bunting and fairy lights. In another part of the city, however, a bright red brick church awaits. I walk to St. Petri, built in 1866 to accommodate the needs of the quickly growing population in the city, where some of the younger Cederstrøm children were baptised. Given its more convenient location, it probably replaced the cathedral as the family's local church. I sit beneath its shadows briefly to rest and people-watch. Then I follow Pedersgata, carefully picking my way around the road construction obstacles, and go down a perpendicular lane – Vinkelgata, at the very end of which is number 28.

In 1865 it was number 882, and home to the family of Peter's son, Fredrick Cederstrøm[[11]], who had made a career as an iron moulder. Born in 1840, he grew up amid the city's industrial boom.

Living in Stavanger during the early to mid-19th century would have held the promise of potential, and the Cederstrøms in Storhaug witnessed these transformations firsthand. With its natural harbour, docks and shipyards, the strategically well-positioned port city had plenty of need for iron and steel foundries. [...] In the 1850s, [the area around Vinkelgata] was a bustling area, with a public square frequented by farmers and their horse-driven carts, vegetable vendors, traders and occasionally a horse market. It was especially lively in the autumn, when fruit sellers from Ryfylke came into town. Historically, it was also the site for speeches and public meetings.[[12]]

On the September afternoon of my visit, however, the houses are almost eerily quiet, and I feel guilty as I surreptitiously take some photographs. The residents of Stavanger are probably used to it, but it still feels a bit like trespassing, and there is no one around to ask permission. Once again, I have an older image to compare, and once again, they are a match.

Prior to its current status as the oil capital of the country, Stavanger of the 19th century faced several challenges. The potato famines of neighbouring countries found their way to Norway in the 1860s, followed closely by the collapse of the herring fishing as well as the shipping industries and the consequent loss of livelihoods. Thousands of Norwegians left for America – 10,000 from Stavanger alone,[[13]] Fredrick and his family included.

Given the city's history with fires, occupation and rebuilding, with only a small percentage of the historic timber houses preserved, I find myself grateful to see two of these homes full of stories still intact. The desire and determination to preserve them are largely credited to the architect Einar Hedén, who served as the city's planner and heritage manager in the late 20th century. It is hard to imagine Stavanger today without the appeal of its historic streets and charming homes. Isn't it often proved that the people who are committed to preserving the past can best envision the future?

Polmanarkivet is sustained by its Stewards

We have made this article free because we believe our family history belongs to everyone. If you value this work, please consider becoming a Steward of the Archive. Your annual contribution ensures these stories are never lost again.

Become a Steward[[1]]: Hatmaking was thriving in Norway at the time, alongside other craft guilds. It is now a protected profession.

[[2]]: Between 150-250 houses were preserved and some can be viewed from the harbour.

[[3]]: Kielland was born in Stavanger, and is considered one of the four literary greats of Norway. He was the mayor of Stavanger from 1891 to 1902.

[[4]]: It is now used as an event venue.

[[5]]: In 2007, a hundred out of approximately 6000 telephone boxes were protected for their cultural importance.

[[6]]: By Vegar Sandholt, bellman, organist and choir master. https://www.vegarsandholt.no/

[[7]]: In the south-west of the city, and includes the city centre and harbour.

[[8]]: At least between 1835 and 1843.

[[9]]: Formerly 205 Gaden til Østervåg.

[[10]]: "19th Century”, Stavanger Museum, Nature | Culture | Childhood, https://www.stavangermuseum.no/en/mitt-stavanger/tiden-5

[[11]]: More specifically, the house was owned by Fredrick's father-in-law. Fredrick married Lisabeth Jacobsdatter in 1860, and she was recorded as living there in the 1865 census along with about 20 residents.

[[12]]: Jake Peterson, Arcadia: Peterson Family History and the Secrets of a Swedish Nobleman (USA: Pictures & Stories Inc., 2022), 78

[[13]]: "19th Century”, Stavanger Museum, Nature | Culture | Childhood, https://www.stavangermuseum.no/en/mitt-stavanger/tiden-5