In 1650, Queen Christina affixed her seal to a letter of nobility (Sköldebrev)[[1]] that cemented the Påhlman family’s noble status. It granted the brothers Johan and Gustaf Polman the right to bear a noble coat of arms and take their place in the House of Nobility. In the letter, the Queen justified this honour by citing the family’s loyalty:

"...that their ancestors have always been esteemed and held as noblemen […] it is [...] not unknown to Us the faithful and good services that these Johan and Gustaf Polman’s Father and Grandfather have demonstrated to the Crown of Sweden…"[[2]]

— Excerpt of the Sköldebrev for Påhlman no. 501, 16 September 1650

At face value, it was a routine recognition of intergenerational service. The grandfather, Jürgen Polman the Elder, had served as a distinguished Governor (Ståthållare) in Livonia, while the father, Jöran Polman the Younger, was memorialised as a loyal servant of the Crown.

But the archives reveal a far less honourable account. Fifteen years earlier, that same "faithful servant" had sold his wife’s property, fled the Kingdom to outrun a dangerous accusation, and had been declared legally "dead" by the local courts. Although this chapter of Jöran Polman’s life brought disgrace, the surviving records suggest his memory was later reshaped to restore honour and preserve the family’s legacy.

The Departure from the Realm

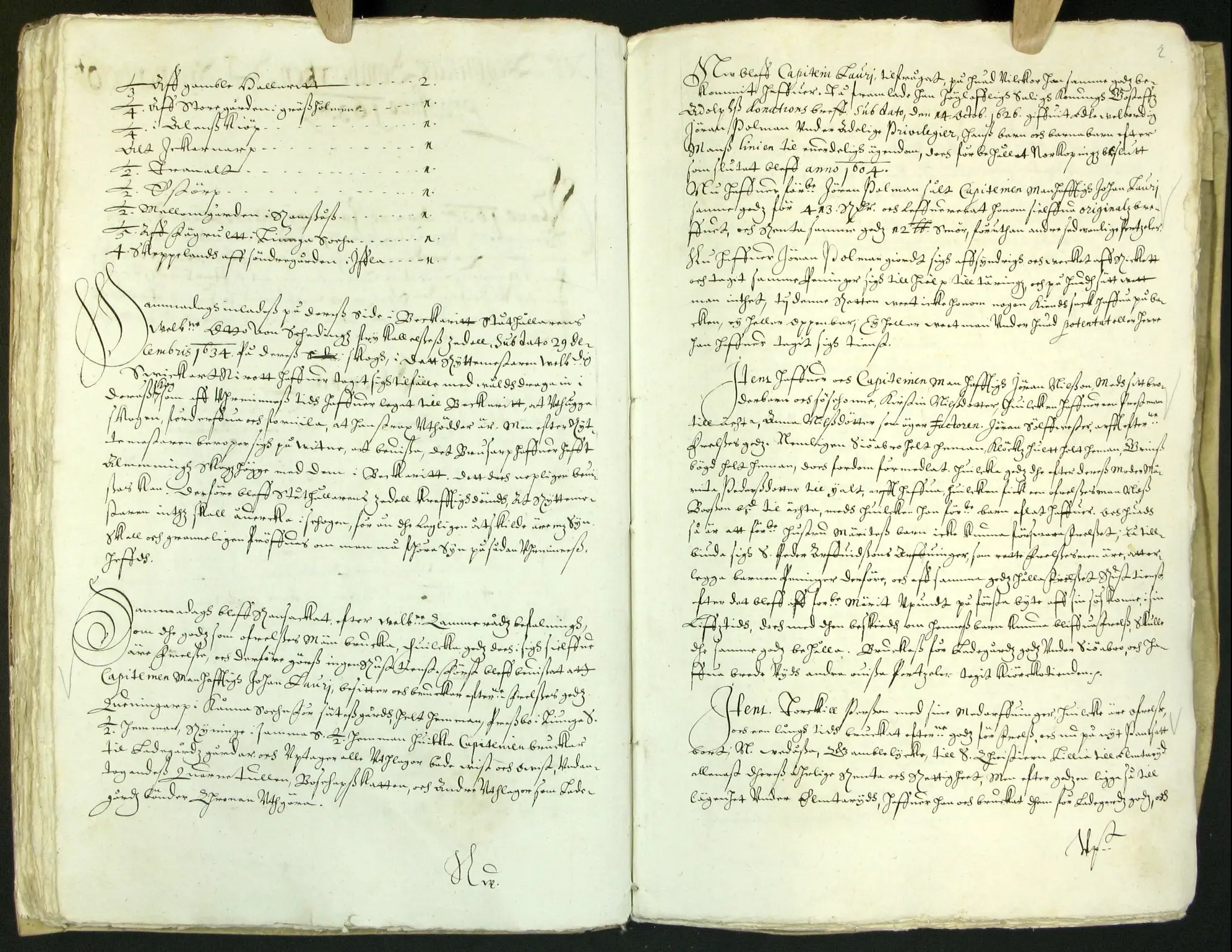

The unraveling began in early 1635. The court was investigating non-nobles (ofrelses män) who were unlawfully occupying tax-exempt noble land. At the centre of this inquiry was the Captain Johan Lauri:

First, it was proven that the Captain, the Valiant Johan Lauri, possesses and cultivates the following tax-exempt noble estates: Queningarp in Kånna Parish as a seat farm (1 full homestead), Pressbo in Ljungby Parish (½ homestead), and Ryninge in the same Parish (½ homestead). The Captain utilizes these as demesne farms and collects all dues…

— Sunnerbo Dombok 1635

Captain Lauri was found to be in possession of several tax-exempt estates, including the seat farm (sätesgård) of Queningarp and half-homesteads in Preßbo and Ryninge.[[3]] When the court demanded to know how a non-noble officer had acquired such privileged property, Lauri produced a deed that exposed a scandal.

He presented a donation letter signed by the late King Gustav II Adolf himself, dated October 14, 1626. The letter granted these lands to "Noble well-born Jöran Polman" and his children and grandchildren for "eternal ownership."[[4]] Crucially, the King’s gift was subject to the Norrköping Resolution (Norrköpings beslut) of 1604, which forbade noble lands from passing into non‑noble hands.

But Jöran Polman, then a Captain in the Kronoberg Regiment, had ignored the decree. In a transaction that violated the terms of the King's gift, the restrictions of the Norrköping resolution, and the rights of his own wife, he had sold the entire parcel of land – and handed over the original letter of donation – to Captain Lauri for 413 Riksdaler.[[5]]

The Sunnerbo District Court recorded the finality of the act. Polman had not just sold the land; rather, he took the cash and ran:

“Now Jöran Polman has made himself departed and left the Kingdom and taken the same money to help himself for sustenance, and for what reason is not known, because this Court does not know him to have any known case pending... Nor is it known under which potentate or lord he has taken service.”[[6]]

— Sunnerbo Dombok 1635

The court’s observation that he had "werket aff Rickett" (worked himself out of the Realm) signals a permanent rupture. His immediate departure with the cash indicates that he was not leaving for duty, but for desperation. Beyond this, the court could say no more. It did not know under which potentate or lord he had taken allegiance, nor for what reason he had left.

What compelled a promising officer to forsake his duty, his estate, and his own household — and flee into the chaos of the Thirty Years’ War?

The Betrayal

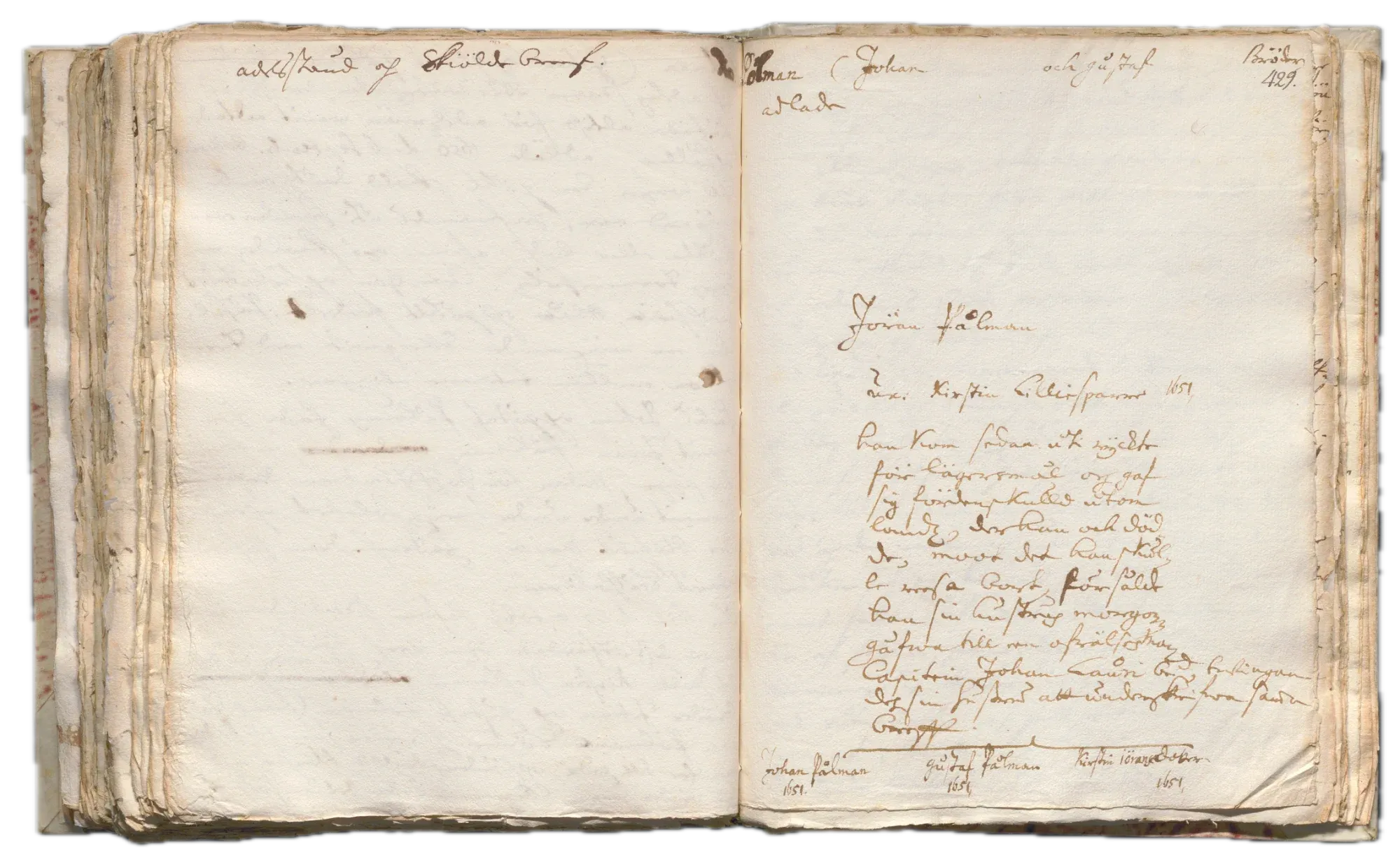

The official court record is silent on the motive, noting only that there was "no known case pending."[[7]] However, a note preserved in the private papers of the seventeenth‑century antiquarian Elias Palmskiöld (MS 232) records the rumour the judges could not answer. Jöran Polman was fleeing the consequences of a sex scandal, specifically "lägersmål" – fornication or adultery.

“He later came into rumor [rüchte] for fornication [lägersmål] and gave himself for that reason out of the country.”[[8]]

— Palmskiöld 232

Lägersmål was a grave offence that could bring social disgrace, financial ruin, and, in some cases, even death.

Within the strict Lutheran moral code of the era, this was a serious accusation. Lägersmål was a grave offence that could bring social disgrace, financial ruin, and, in some cases, even death.[[9]] The "rumour" implies Polman fled before the matter could reach the courts.

The true nature of this lägersmål, however, was a capital matter. The woman named in the rumour was Beata Lilliesparre — the first cousin to Jöran's own wife. In October 1635, at the exact moment Jöran was liquidating his assets and fleeing the realm, the Västbo district court opened an investigation into Beata Lilliesparre for the crime of barnamord (infanticide).

The official transcripts reveal that no witness would speak on the record, and the Vice-Governor documented what he heard only after the formal session had concluded:

"Regarding any man's secret intercourse with Mrs. Beata Lilliesparre, no one will or dares to reveal such a thing at the court session, but on the 4th of October which was the day after the court session was concluded, the well-born Vice-Governor Peder Månsson Lood related... that common talk goes in the district that Captain Jöran Pålman [Polman] at that time was courting Mrs. Beata Lilliesparre at Sunnaryd..."[[10]]

The gossip had spread so widely that it reached the local clergy. The court record notes that the late vicar provost of Bolmsö traveled to Beata's estate to confront them, delivering an ultimatum: "What the thousand devils kind of living shall this be, either it must go fast with the courtship and the marriage, or it must come to an end." The vicar’s ultimatum lays bare the true stakes of Jöran’s sudden departure. He was fleeing a potential death sentence for incestuous adultery and possible complicity in infanticide.

The Palmskiöld note reveals one further consequence. The lands Jöran sold to the non-noble Captain Lauri were legally his wife’s morning gift (morgongåva)[[11]] – Christina Lilliesparre’s guaranteed financial security. To sell them, he needed her signature. Palmskiöld records the coercion involved:

“[When] he was to travel away, he sold his wife's morning gift to a non-noble man, Captain Johan Lauri, and conditioned [betingade] his wife to sign the same Deed!”[[12]]

— Palmskiöld 232

The word "betingade" implies coercion. To fund his escape, Jöran Polman compelled his wife to sign away the very property meant to secure her future.

The Civil Death

Two years later, Christina Lilliesparre was left to manage the fallout of Polman's abandonment at the family seat of Ugglansryd. The 1637 Sunnerbo court records offer a glimpse into the confusion following his disappearance. A creditor, Måns Jonszon, appeared before the court, demanding payment for a debt of 300 Riksdaler. The promissory note was missing, forcing a search through the personal effects Jöran had left behind:

“But since the provost received neither receipt nor the promissory note back, but the promissory note was found in Polman's belongings [gömmor] the matter is doubtful...”[[13]]

— Sunnerbo Dombok 1637

The word "gömmor" (hiding places) evokes the urgency of his departure; Polman had fled so quickly that vital documents were left hidden in chests or drawers.

With Polman beyond their reach, the court took an extraordinary step to protect the estate. They declared the accounts between Polman and his creditor to be legally finished:

“Item the account Måns Jonszon's authorized representative presented, [is] voided, as well as all writings new and old which passed between well-born Jöran Polman and Måns Jonszon, are dead [döde], and in all letters cancelled.”[[14]]

— Sunnerbo Dombok 1637

Jöran Polman was declared legally dead. His debts were voided, and his letters cancelled. The state had washed its hands of him.

Don’t want to miss the next chapter?

Become a Member of Polmanarkivet for free to get new research and stories delivered directly to your inbox the moment it's published.

The Silent Years (1636-1647)

Because the Sunnerbo court declared his debts void, some historians[[15]] have assumed that Polman died shortly after fleeing Sweden in 1635. However, the Regency Council believed otherwise. On 10 December 1641 – six years after Polman’s departure – the Regency Government of Queen Christina confirmed the family’s noble estates in Livonia[[16]] in response to a petition from Jürgen Polman’s heirs.

The document lists the heirs of the late Governor Jürgen Polman in strict order of precedence:[[17]]

Her Royal Majesty [Queen Christina] together with the Swedish Realm's respective Guardians and Government, Make known, how on behalf of the Late Jörgen Pohlman’s surviving Widow, Jöran, Christina, Gertrudt, Barbro, Catharina, Clas, Henrich, Johan, and Friderich Pohlman...

— Excerpt from a confirmation letter from the Regency Government dated December 10, 1641

The inclusion of his name in a formal land grant strongly suggests that he was still alive in 1641. The Crown would not list deceased individuals among living heirs, since doing so could jeopardise the validity of the grant. His presence in the document shows that, although Polman was a fugitive from local justice in Småland, he remained legally recognised in the family’s Baltic estates. This is likely a reflection of the administrative separation between Sweden’s provinces and its Livonian dominions.

While Swedish muster rolls cease to record him after 1629, the archivist Palmskiöld preserves a different version of his career path. In biographical notes written toward the end of the 17th century, Palmskiöld writes:

“The aforementioned Johan and Gustaf Påhlman’s father has been Jöran Påhlman, who [served] first as Page, then as Court Junker, from there came under the war-people [the army], and advanced there [and] Became Major...”[[18]]

— Palmskiöld MS 232, p. 425

This document provides the earliest known written source for the Major rank found in later genealogies. Since Polman could not hold a commission in the Swedish Royal Army while fleeing its laws, the rank points most plausibly to service abroad. His missing years were likely spent either in the family’s Baltic territories or in the Protestant armies of the Continent.

It is possible that in the chaos of the Thirty Years' War, the exiled Polman found service and promotion under a foreign flag. His experience as an officer may have allowed him to disappear into mercenary or auxiliary service. It is also possible that the rank reflects later memory – a retrospective elevation in genealogies as the family sought to reframe his life after disgrace.

The Major in the Sacristy

Jöran Polman never returned to Sweden alive. He died abroad sometime in the 1640s. By 1648, his wife Christina Lilliesparre appears in the Sunnerbo court records as “a sorrowful and much distressed widow” (en sorgefull och mycket bedrövad änka).[[19]] In seventeenth‑century court language, this phrasing typically indicated recent bereavement. Recorded twelve years after Polman’s departure, the court entry marks the moment when his long absence was formally acknowledged as death. Later genealogists record the outcome succinctly: Palmskiöld notes that he "gaf sig fördenskull utom landz, der han och död är" (gave himself for that reason out of the country, where he is also dead),[[20]] while Elgenstierna likewise states that he died “abroad.”[[21]]

Despite dying on foreign soil, he was not left there. In a final act of family reclamation, his body was repatriated to Sweden. Repatriating a body from the continent or the Baltic provinces required significant financial and logistical resources. That Christina Lilliesparre orchestrated this return implies that the family had regained enough resources to secure his burial at home – a remarkable turn of events for an estate that, just years earlier, had been besieged by creditors and forced to void its accounts. Returning his body to Sunnerbo affirmed the family’s standing within the parish community.

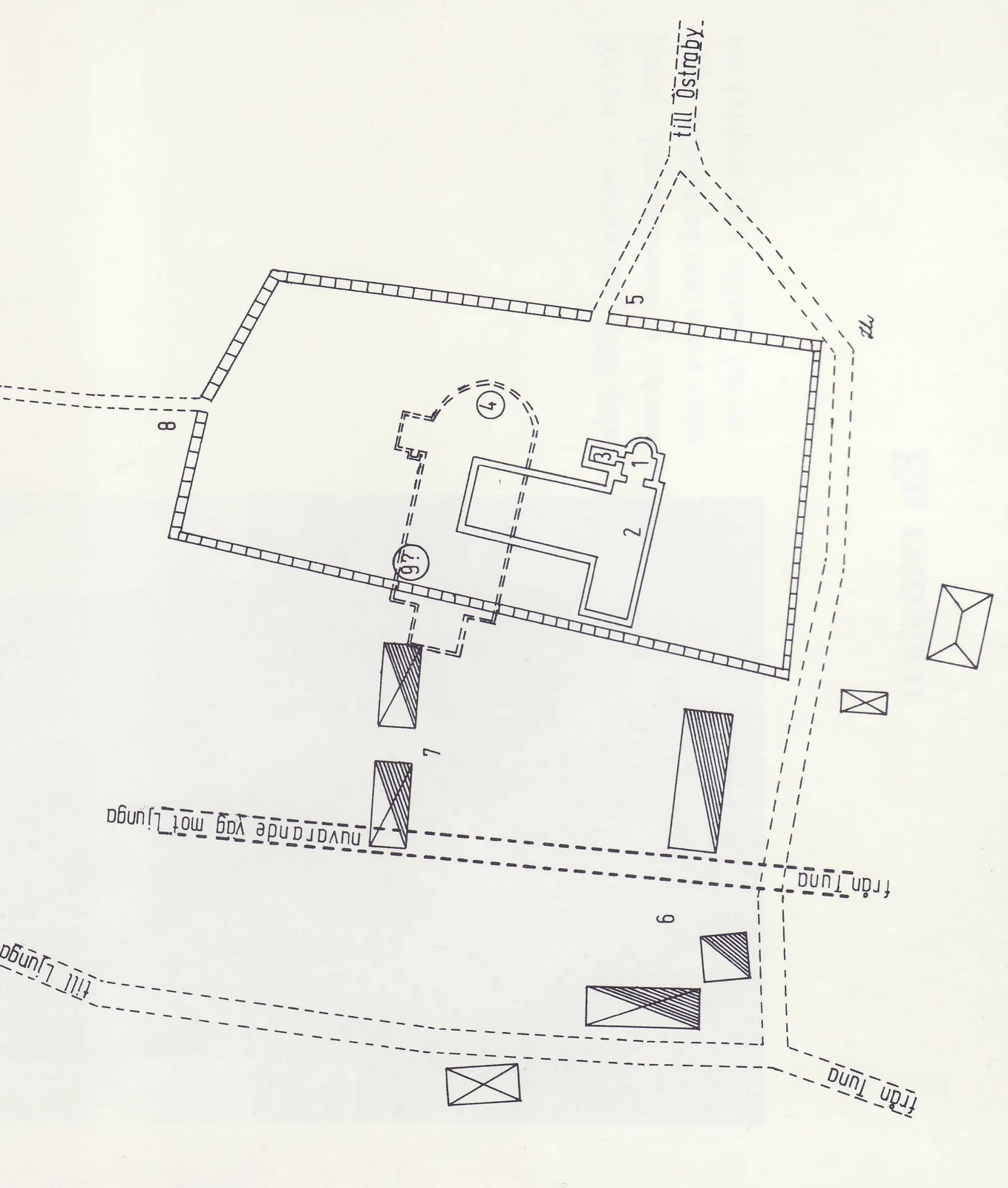

Her success is recorded in the church itself. The manuscript Archivum Smolandicum (No. 306), which catalogs local noble estates and monuments, explicitly lists a grave for the Påhlman family located in the church's most significant room:

"One [grave] in the Sacristy belonging to the Påhlman family."[[22]]

— Archivum Smolandicum No. 306

The antiquarian Samuel Rogberg (1770) confirms this by stating "...in the Church [are] 2 walled tombs, of which one belongs to the first-mentioned family [Påhlman].[[23]] While any inscriptions on the graves remain lost, compiled genealogies, including Elgenstierna, record that Polman was buried within this walled tomb of the sacristy.[[24]][[25]]

Polman may have fled Sweden to escape judgment for a mortal sin, but he was ultimately laid to rest in the church's most sacred ground.

Fig. 5 - Left: The current Ryssby Church, built 1840-1844 adjacent to the original site (Photo: Bernt Fransson, Lindås). Fig. 6 - A plan of the medieval church overlaid with the modern footprint. The marker #3 identifies the Påhlman family tomb situated within the old sacristy, where Jöran Polman was buried.

Burial within the sacristy was a privilege reserved for the parish elite.[[26]] That Jöran Polman died abroad yet was buried in the sacristy implies a deliberate effort to physically reintegrate him into the family he had abandoned. The location serves as a stark correction to the court records of 1635: Polman may have fled Sweden to escape judgment for a mortal sin, but he was ultimately laid to rest in the church's most sacred ground.

Lady Kirstin of Ugglansryd

The final word on Jöran Polman belongs not to the man who fled, but to the woman he left behind – Christina Lilliesparre af Fylleskog

She did not merely survive her husband’s abandonment; she took control of the household, the estate, and the family’s future. In the years following his departure, she appears in the legal record as “Lady Kirstin of Ugglansryd” — asserting property rights, defending disputed crofts, and managing the family's affairs in her own name.

She would live to see her sons ennobled by the Queen in 1650. Johan and Gustaf, both in the military, were knighted at Stockholm Castle on 16 September, taking on the name Påhlman on 3 October under No. 501. The sköldebrev itself celebrates their service:

“Now, whereas Our faithful servants, the honest and valiant Johan and Gustaf Pohlmän, have now for a time served Us and the Crown of Sweden in the military, both under the Cavalry and the Infantry, and therein — as has been testified of them by their Commanders — have conducted themselves faithfully, well, and manfully...”

— Excerpt of the Sköldebrev for Påhlman no. 501, 16 September 1650

The sköldebrev also enshrined Jöran Polman not as a deserter of the Realm, but as a “faithful servant” of the Crown. By the time his sons entered the nobility, the family narrative had been rewritten. The disgraced Polman of 1635 had become the ‘faithful servant’ Påhlman of 1650 — a new name inscribed in the Crown’s archives as one of honest and loyal service.

Christina Lilliesparre's hand in this retelling is unmistakable. She defended the estate, settled its debts, brought her husband’s body home for burial in the sacristy, and guided her children into positions where their loyalty could be recognised. By burying her husband and the scandal of 1635 beneath the stone of the church, she ensured that her sons would inherit a legacy of service rather than shame. The honour restored was not only her husband’s; it was the survival of the line itself.

Polmanarkivet is sustained by its Stewards

We have made this article free because we believe our family history belongs to everyone. If you value this work, please consider becoming a Steward of the Archive. Your annual contribution ensures these stories are never lost again.

Become a Steward[[1]]: Sköldebrev (literally "Shield Letter") is a Patent of Nobility issued by the Swedish Crown. It is the formal legal document that grants a person and their descendants noble status, including the right to bear a family coat of arms and take a seat in the House of Nobility.

[[2]]: Queen Christina to Johan and Gustaf Polman, "Sköldebrev för adliga ätten Påhlman, nr 501," September 16, 1650, Riddarhuset (House of Nobility), Stockholm, Artefact Collection, Inventory No. 01:31, Archive ID 11-1398.

[[3]]: The estate names listed in the 1635 court record are archaic spellings. Queningarp corresponds to the modern Kvänjarp; Preßbo to Prästeboda; and Ryninge to Rönninge.

[[4]]: “Påhlman nr 501”, Adelsvapen-Wiki, https://www.adelsvapen.com/genealogi/Påhlman_nr_501, accessed: 17 March 2022.

[[5]]: Determining a modern equivalent for 17th-century currency is difficult, but in terms of purchasing power, 413 Riksdaler was a substantial sum. It represented approximately eight years of wages for a private soldier or fifteen years of earnings for an unskilled laborer. It was probably enough cash to purchase a modest farm or sustain an officer for several years abroad.

[[6]]: Sunnerbo Häradsrätt, Dombok 1635, Göta Hovrätt - Advokatfiskalen Kronobergs län, EVIIAAAD:12 (1635-1640), Bild 38/sid 2 (AID: v49320.b38.s2, NAD: SE/VALA/0382503).

[[7]]: Ibid.

[[8]]: Elias Palmskiöld, Genealogiae Sveo-gothicae, Tomus XLI, Litt. P, Pars 3, MS Palmsk. 232, p. 425, Palmskiöldska samlingen, Uppsala University Library, Uppsala.

[[9]]: Jan Sundin, För Gud, Staten och Folket: Brott och rättskipning i Sverige 1600–1840 (Stockholm: Rättshistoriskt bibliotek, 1992); see also Jonas Liliequist, "Brott, synd och straff: Tidelagsbrottet i Sverige under 1600- och 1700-talet," in Historisk Tidskrift (1991). In 1608, Sweden formally incorporated Mosaic Law, dramatically increasing the severity of sexual crimes. Lägersmål (fornication) and hor (adultery) carried severe penalties ranging from heavy fines to death.

[[10]]: Västbo Häradsrätt. Court Protocol regarding Beata Lilliesparre, October 2–3, 1635. Göta Hovrätt - Advokatfiskalen Jönköpings län (E, F, G, H, N) EVIIAAAC:8 (1633-1649), Image 560 / Page 33. AID: v190284.b560.s33, NAD: SE/VALA/03825/03. ArkivDigital.

[[11]]: The Morgongåva (Morning Gift) was a provision in medieval and early modern Swedish law, given by the groom to the bride on the morning after the wedding. Unlike a dowry, the Morning Gift was intended specifically to support the wife during widowhood. While the husband managed the land during his lifetime, it remained her separate property; he was legally forbidden from selling or mortgaging it without her consent.

[[12]]: Elias Palmskiöld, Genealogiae Sveo-gothicae, Tomus XLI, Litt. P, Pars 3, MS Palmsk. 232, p. 425, Palmskiöldska samlingen, Uppsala University Library, Uppsala.

[[13]]: Sunnerbo Häradsrätt, Dombok 1637, Göta Hovrätt - Advokatfiskalen Kronobergs län, EVIIAAAD:12 (1635-1640), Bild 155/sid 9 (AID: v49320.b155.s9, NAD: SE/VALA/0382503).

[[14]]: Ibid.

[[15]]: See: J.A. Almquist; Frälsegodsen i Sverige under storhetstiden.

[[16]]: Now modern Latvia and Estonia.

[[17]]: See "Letter of Confirmation regarding Oethel," December 10, 1641, inRiksarkivets ämnessamlingar, Personhistoria, Vol. P 26, "Polman," Bildid: A0070062_00310, Riksarkivet, Stockholm.

[[18]]: Elias Palmskiöld, Genealogiae Sveo-gothicae, Tomus XLI, Litt. P, Pars 3, MS Palmsk. 232, p. 425, Palmskiöldska samlingen, Uppsala University Library, Uppsala.

[[19]]: Sunnerbo Häradsrätt, Dombok 1648, Göta Hovrätt - Advokatfiskalen Kronobergs län, EVIIAAAD:15 (1648-1649) Bild 65/sid 21 (AID: v49323.b65.s21, NAD: SE/VALA/0382503)

[[20]]: Elias Palmskiöld, Genealogiae Sveo-gothicae, Tomus XLI, Litt. P, Pars 3, MS Palmsk. 232, p. 425, Palmskiöldska samlingen, Uppsala University Library, Uppsala.

[[21]]: Gustaf Elgenstierna, Den introducerade svenska adelns ättartavlor, vol. V (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, 1930), s.v. "Påhlman, nr 501."

[[22]]: Gahm Persson, "Beskrifning öfver Ryssby Pastorat" [Description of Ryssby Pastorate], Archivum Smolandicum, Vol. 07, Document no. 306, scanned pp. 333–340, Växjö Stifts- och Landsbibliotek, Växjö, https://hosting.devo.se/vaxjo/BookView?BookId=23.

[[23]]: Samuel Rogberg, Historisk Beskrifning om Småland (Karlskrona: 1770), 427.

[[24]]: Gustaf Elgenstierna, Den introducerade svenska adelns ättartavlor, vol. V (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, 1930), s.v. "Påhlman, nr 501."

[[25]]: While the original Sacristy was demolished in 1844, a 2007 survey by Smålands Museum noted a singular 17th-century limestone slab located in Block C of the current cemetery. Described as possessing "the highest cultural-historical value" but being "heavily worn and difficult to read." Although unlikely, this displaced marker could be the Polman grave moved during the demolition. See Pernilla Wandestam, Ryssby kyrkogård: Kulturhistorisk inventering och bevarandeplan, Smålands museum rapport 2007:119 (Växjö: 2007), 16.

[[26]]: Peter Carelli, Tills döden skiljer oss åt: En arkeologisk undersökning av gravskick och sociala strukturer i Linköping under medeltid och tidigmodern tid (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 2001); see also Göran Malmstedt, Bondetro och kyrkoro: Religiös mentalitet i stormaktstidens Sverige (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2002). In 17th-century Swedish Lutheran tradition, the church floor was a mapped hierarchy of social status. Burial within the Koret (Chancel) or Sakristian (Sacristy) was a privilege strictly reserved for the nobility and high clergy, symbolising their proximity to the sacred.