“Here and in front of the court, his Royal Highness’ servant Jöran Polman pleads plaintively to Johann Schönbeck’s friend, the cellar boy Hans Wulf, that [Wulf] accused him of being a thief, fraud and a dishonest man, [and] requested that the court handle this matter and if [Wulf] would not be able to prove it, he must get a fitting punishment. Then Hans Wulf answered that Poleman puts it mildly…”[[1]]

— Stockholms Tänkeböcker Från År 1592

Thus begins a bizarre tale involving the future captain Jöran Polman – one that, unlike his portrait, paints him in a rather unflattering light. The setting of the scene was a tavern, more accurately Johan Schönbeck’s cellar. It appears in records from 1618 until around 1629, and was located in Gamla Stan, possibly in the vicinity of Stortorget.[[2]] The date of the incident was 20 July 1618, so it may have been a new and happening place at the time.

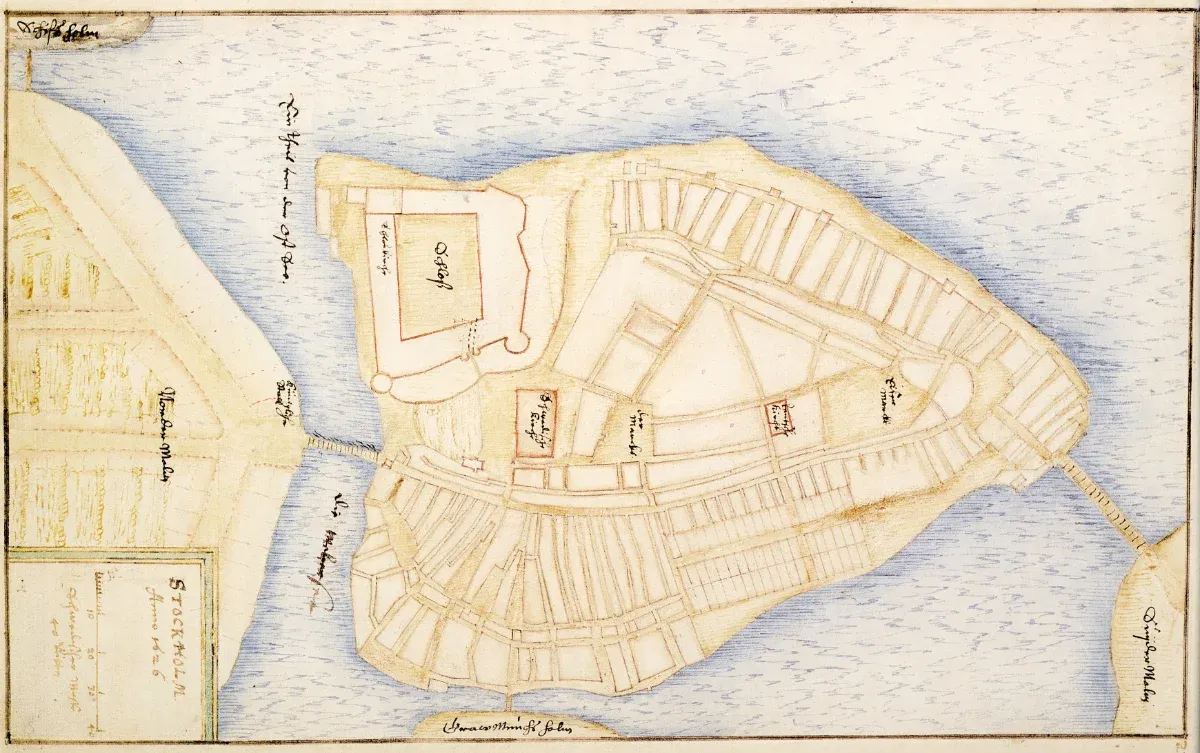

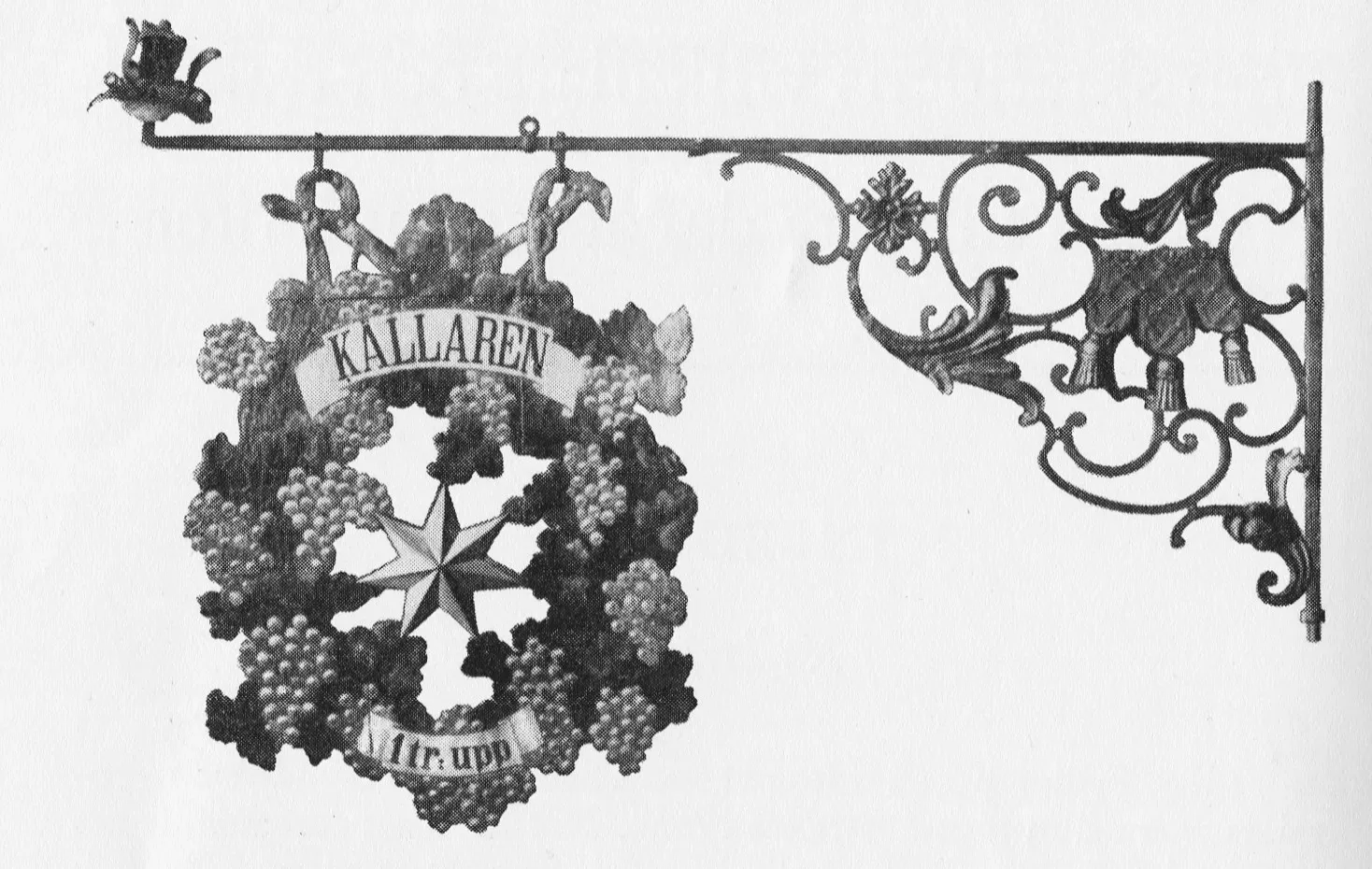

Though venues to drink had existed since at least the middle ages in Sweden, inns, taverns and coffee houses were sprouting in 17th century Stockholm, “the city between the bridges”.[[3]] According to a decree by Charles IX in 1605, only six inns and two walk-in kitchens were allowed to be open in the city[[4]] – an improvement from the previous century when Johan III had declared that cellars would "be destroyed and become nothing".[[5]] Distinctive signs marked these establishments, representing their names: Tre Kronor (three crowns), Blå Örnen (a blue eagle), Förgyllda Lejonet (a gilded lion), Gripen (a griffin), Värdshuset Solen (the sun), Värdshuset Månen (the moon), Gårköket Farkena (a pig) and Källaren Stjärnan (a gilded star).[[6]]

I will punch you in your eyes so that the devil will take you. - Jöran Polman

The sale of alcohol was already controlled by legislation to protect professions related with trade, but was not very effective in controlling the culture of alcoholism prevalent at the time, as booze could be resold privately. In 1604, many were summoned and fined for not complying with limitations.[[7]] By 1623, there would be some restrictions in place at such establishments:

“All taverns and wine cellars were warned that no one was allowed to sell beer or wine in the cellars after the clock has struck 8 in the evening [and] unchristian behaviour, including screaming and shouting, which through this drunkenness prefaces itself, must be silenced and abolished."[[8]]

On that summer evening in 1618, however, a 21-year-old Polman arrived at the tavern alone. He requested from the cellar boy, was provided with and consumed, in quick succession:

- “nice” dark beers

- a taste test

- food

- Rostock beer

- four varieties of Spanish wine

- jugs of wine from the Canary Islands

Fig. 3 - The property Atlas 8 where Förgyllda Lejonet was located, 2019, photograph. Image by Holger Ellgaard (CC BY 4.0). Fig. 4 - Erik Dahlbergh (1625-1703), illustration of Södra Bankohuset with the sign of Blå Örnen, 1691, etching. Image by Wikimedia Commons (PDM). Fig. 5 - Källaren Stjärnan sign from the mid-18th century, 1900-1910, illustration. Image by Nordiska museet (PDM). Fig. 6 - The basement room likely where Värdshuset Månen's wine cellar was located, 1940, photograph. Image by Stockholm City Museum (PDM).

In all, Polman, joined by some equally rowdy friends, consumed 3 pints of mumma (Christmas beer), 4 pints of beer and 2 pints of Canary Island wine for the yet unpaid price of 2 thalers. “Then he said he wanted to visit a beautiful place, if he dared, that had lovely women,” upon which the cellar boy, Hans Wulf, had had enough, and refused more drinks without payment. Incensed, Polman became abusive, calling him “kahle bernheüter”[[9]] and threatening to “punch you in your eyes so that the devil will take you”, causing Wulf to lock himself in the cellar for self-preservation.

Don’t want to miss the next chapter?

Become a Member of Polmanarkivet for free to get new research and stories delivered directly to your inbox the moment it's published.

“This excessive drinking, where it obviously was a social error for the individual to show himself too influenced by alcohol, was a way of showing masculinity by appearing uninfluenced, but also the ability to control the own body. This was a rather gruesome performance of male identity and social bonding, since to avoid, excuse yourself or even to quit a drinking session would probably be viewed as an insult towards the people at the table and as a sign of weakness.”[[10]]

— Alexander Engström, "Bacchus and social order Noble drinking culture and the making of identity in early modern Sweden"

Before I leave here, I will deal with you, and then you will remember me as long as you live. - Jöran Polman

Given what had already occurred, it's unclear whether Polman was concerned in the least with keeping up appearances. After calming down slightly, he offered his honour for an extension in payment until the following day. However, he refused to divulge his identity, and insisted on the host's involvement, who obliged. Although he was not acquainted with Polman in the slightest, and a drunk Polman even less, the host wrote up a bill and asked Polman to leave before the brawl could escalate, with the promise of paying his dues the following day. Polman had other ideas, and instead made the choice to resume his verbal assault and demands for booze, which were denied:

“At the same time H. Claes Biälke's servant, who was sitting at the other table, requested that the cellar boy should pour them a jug of beer, which he did. As he was about to close the cellar hatch again, Polman took hold of his beard and punched him in the face with one of his hands, tore half of his beard off with his other hand, and his comrade came back with a drawn sword. They both wanted to kill him there in the cellar, if it weren’t for H. Claes Bjälke's servant had prevented them.”

— Stockholms Tänkeböcker Från År 1592

Fortunately, in this case, Hans Wulf's life was spared.

The Stockholm Tänkeböcker shows that deadly violence was significantly more prevalent in the Middle Ages, with occurrences up to a hundred times greater than today. Even in 17th-century Stockholm, fatal brawls between men, often involving alcohol, were frequent. A mere insult to one’s honour could quickly lead to confrontation — and death.

The host of the establishment understandably kicked the party out, and then dragged them to court. Unfortunately such incidents were not uncommon; entitlement and violence were a part of the everyday life and social structure in Sweden, and were normalised as a method of control:

“At the same time, the superior had responsibility and would protect his subordinate. The king would lead and protect his people, the patriarch his wife and children, the priest his congregation. The subordinates were expected to obey and trust the one who led. The children could be disciplined and the farmhand reprimanded with violence. The violence would nurture and promote order in the household. Moderation was a virtue, but it was not so easy to determine how much violence was permissible. Intoxication could be a mitigating circumstance or if the violence had been provoked.”[[11]]

— Linköpings Historia

This had particular significance for the nobility, allowing them to assert their superiority and status, especially over members of lower classes in the social hierarchy. This might perhaps explain why Polman – an aspiring military man and noble – comfortably abandoned respectful behaviour towards the cellar boy, quick to abuse and assault him, while retaining some politeness toward the host of the tavern. Such behaviour was also characteristic of soldiers, although it would only be the following year that he started working as a bursch:

“Drinking courageously and valiantly is frequently compared to the honourable pursuits of battle, where honour and loyalty to King and country was held in a very altruistic way, which even should overpower the love the warrior held to his wife. By distinguishing oneself in drinking as on the battlefield was an honourable task and pursuit which helped to promote the ideals of the nobility’s relation to violence.”[[12]]

— Alexander Engström, "Bacchus and social order Noble drinking culture and the making of identity in early modern Sweden"

Fig. 8 - Erik Palmstedt (1741-1803), Stockholm's former town hall (rådstugan), 1768, illustration. Image by Kungliga Biblioteket (PDM). Fig. 9 - John Beer (1853-1930), a session at Stockholm city court, 1877, wood-engraving. Image by Wikimedia Commons (PDM).

No matter his reasons, Polman's actions displayed a desire to enforce masculinity and superiority, which were not looked upon too kindly in court. His friends and allies – Otto Tremo and Johan von Nennemund – testified that the cellar boy had accused him of being a “fraud”, a “thief” and an “indecent man”. Wulf blamed this on the heat of the moment.

Usually under the rule of law, “those who could pay for themselves got away with a fine, while others could be punished corporal[ly]. The court tried to find practical solutions [...] but having a high status in society with many good men and being a man favored the accused.”[[13]] In this case, however, Polman was sentenced to “in edsöre”[[14]] (old Swedish law) and was required to pay a fine of 40 marks and the tavern his dues in full. Wulf also received a punishment of a fine of 12 marks. However, luckily, “their honour and respect are completely intact".

Polman would go on to have an industrious career. The following year, in 1619, he started his military career as a noble bodyguard, then became a hovjunkare, and a captain in 1623, as well as chamberlain to King Gustavus Adolphus. His military achievements brought fame, and his portrait adorns the walls of Skokloster Castle to this date. His marriage brought him status and a manor; he was granted noble privileges in 1626, and promoted to the rank of major before his death. Perhaps the drunken brawl of his youth was a blip on his record, or maybe it was in keeping with social behaviours of the time.

Polmanarkivet is sustained by its Stewards

We have made this article free because we believe our family history belongs to everyone. If you value this work, please consider becoming a Steward of the Archive. Your annual contribution ensures these stories are never lost again.

Become a Steward[[1]]: Olsson, Sven, and Naemi Särnqvist, eds. Stockholms Tänkeböcker Från År 1592. Vol. 12 (1620-1621). Stockholm: Stockholms Stadsarkiv, 1976. http://libris.kb.se/bib/129451.

[[2]]: Fredrik Ulrik Wrangel, “Härbärgerare och gästgifvare i Stockholm från 1419 till och med 1544 och från 1582 till och med 1641”, Stockholmiana I-IV (Stockholm: Norstedt & Söners Förlag, 1912) https://runeberg-org.translate.goog/wrangsto/?_x_tr_sl=sv&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

[[3]]: Wrangel, “Stockholm's inn and wine cellar at the beginning of the 17th century”, Stockholmiana I-IV

[[4]]: In 1602, it was the wine cellars owned by Stadens, Baggarnes, Benicks, Hans Klawers, Hans Meijers and Henrik Danitz, and nine illegal cellars were shut down.

[[5]]: “As for the many wine cellars and beer taverns, they were all to be closed down, and then only the other cellars that have been in use for years were to be cleaned on the mines or in the city, namely: 1) The city's wine cellar (which would be exempt from the excise duty); 2) Baggarne's cellar (which would be excise-free, even if the Baggarne were added, but the others, who hold a party in there, would constitute the excise tax on at least half of all drinks, where in the basement was drained); 3) Jören Benick and 4) Petter Wernick (would constitute all excise duty). Tänkeboken. Fol. 22

[[6]]: Wrangel, “Härbärgerare Härbärgerare och gästgifvare i Stockholm”

[[7]]: Tänkeboken 1604, Fol. 200

[[8]]: Tänkeboken for 1623 (Fol. 103 and 104)

[[9]]: Translator's note: a sort of insult, “bald inept or lazy person”

[[10]]: Alexander Engström, “Bacchus and social order Noble drinking culture and the making of identity in early modern Sweden”, 2013, Historiska Institutionen, Master's thesis

[[11]]: “1500-1700", Linköpings Historia, https://linkopingshistoria.se/1500-1700/1604-1700/

[[12]]: Engström, “Bacchus”

[[13]]: Linköpings Historia

[[14]]: Or "breach of the king's peace", an old Swedish law that restricted feuding between nobles. It was the king's promise to uphold peace in the realm and anyone who went against that consequently became the enemy of the king personally and would be warned or punished.