The Stalwart Captain

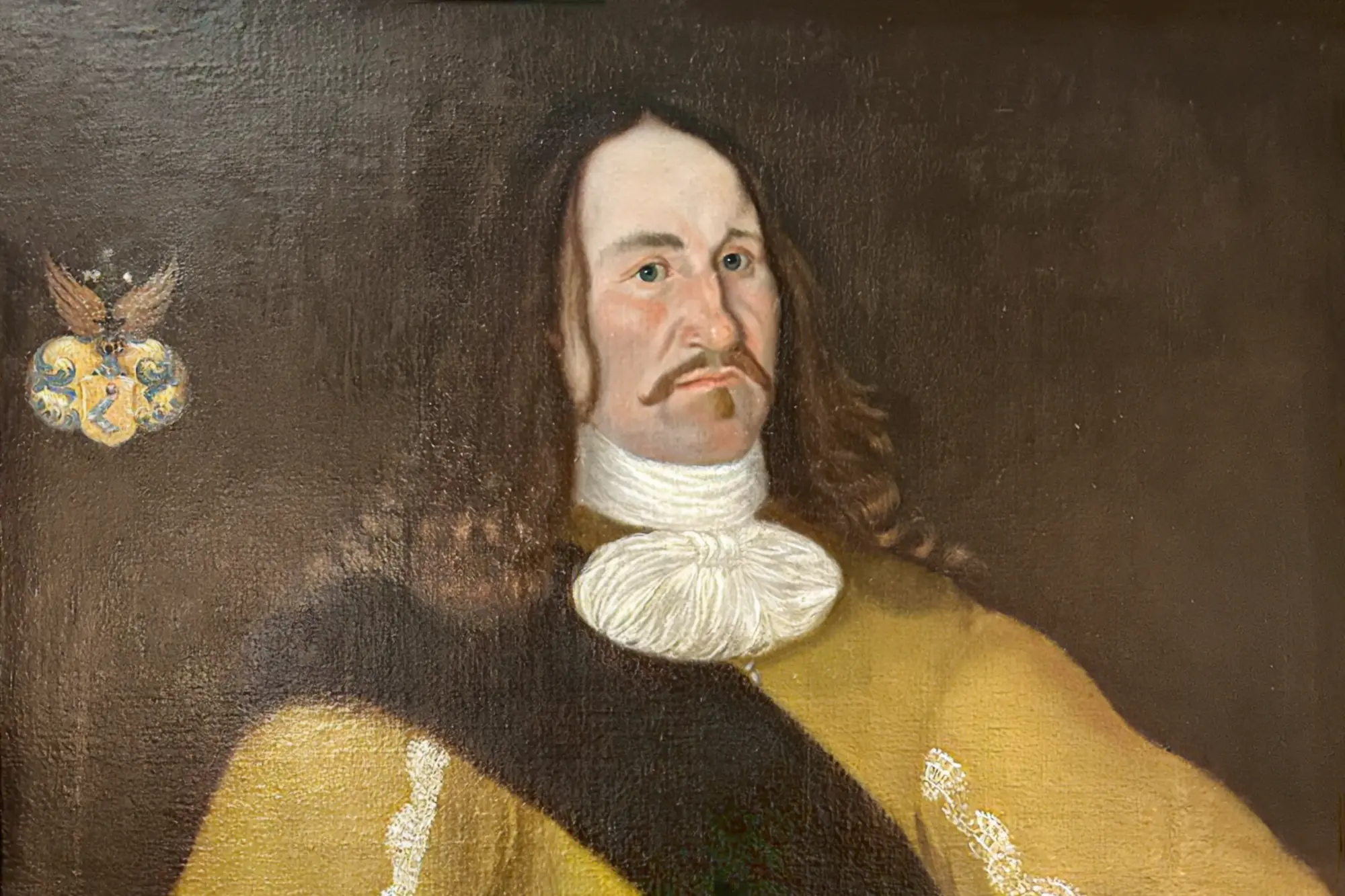

Anders Otto Påhlman was a nobleman who served in Småland’s cavalry regiment. He was born at Ugglansryd on 13 August 1740, the seventh child of Lieutenant Colonel Carl Gustaf Påhlman and Christina Elisabet Renner. In 1752, Anders Otto joined the regiment as a corporal[[1]] – at the time, the age limit for volunteering indicated only that one had to be “old enough to handle a musket.”[[2]] He was 17 when his father died of a stroke.

In 1765, Anders Otto was a member of the princely livdrabant (bodyguard), which was similar to a royal guard. He retired from his military career due to illness[[3]] in 1772 as ryttmästare or cavalry master, which corresponded to the rank of captain, and in the same year inherited the manor Ugglansryd from his father. On 9 September 1774, he married his brother-in-law’s niece Christina Margareta Unge, sometimes known as Greta Stina, in Hemmesjö med Tegnaby, Kronobergs län. She was the daughter of lawyer Per Andersson Unge and Sofia Cornelia Stålhammar.

Anders Otto and Christina had eight children – Per Gustaf (1775-1776), Carl Otto (1776-1806), Johan Fredrik (1778-1779), Anders Adam (1779-1851), Christina Sofia (1781-1864), Göran (1782-1830), Margareta Elisabet (1783-1856) and Emerentia (1784-1870) – two of whom died in infancy.

In 1783, a sizeable corps de logis was constructed at Ugglansryd, with “the old, typical manor style, broken roof, without frontispieces”, perhaps to better accommodate the growing family. The new construction was a vision:

It has a particularly beautiful location on the shore slope near Lake Stensjön, which here presents a delightful tableau, framed as it is by a beach, which is crowned by alternating deciduous and coniferous forest, and so with a main part of the lake’s extensive water surface, which is interrupted by a number of cover islets, which lie scattered off the beach and put relief on the whole. A long peninsula, overgrown with stately deciduous trees, stretches out into the lake from the park that surrounds the corps de logis, and an old legend tells that this peninsula would [have been] the beginning of a magnificent bridge, which one of the estate’s [former] owners worked on in order to connect Ugglansryd with Stensnäs on the other side of the lake.[[4]]

Anders Otto was widowed in 1784, with young children to care for. Christina died shortly after giving birth to their daughter Emerentia, either from childbirth or a stroke, at the age of 27.

Several pieces of evidence point to a lesser-known story concerning this noble family. Stina Jönsdotter[[5]] worked at Ugglansryd as a maid and lived at Metaretorpet, a cottage on the premises. Between 1791 and 1802, she had six children with Anders Otto, named Johannes (1791-1848), Brita Stina (1794-1863), Anna Greta (1796-1879), Sofia (1799-1801), Peter (1800-1874), and Kristina (b. 1802). Johannes was born when Stina was 20, and Anders Otto was twice her age. They followed the patronymic naming system prevalent in Sweden at the time[[6]] – the father’s baptismal name with the suffix for son or daughter, thus “Andersson” and “Andersdotter.”

Certainly there would have been a disparity of power in Anders Otto and Stina’s relationship, but on his part, there seemed to be a sense of responsibility and perhaps even genuine care. At the time, it was legally a crime to have children out of wedlock, with the possibility of punishments such as whipping or jail time.[[7]] Additionally, the father of a child born out of wedlock was required to pay a fine, with the amount increasing exponentially with the number of children born – but there was no obligation to continue paying thereafter. Anders Otto, however, contributed financially towards his children’s upbringing, and made arrangements for them to be supported until they came of age.

In 1798, Anders Otto sold Ugglansryd, ending a chapter in the family’s history.[[8]] He may have then moved to Agunnaryd, with Stina accompanying him there or residing in the vicinity, as their later children were all baptised in Agunnaryd. Stina was not betrothed, nor did she have any prospects – as a nobleman, this would have been unthinkable for Anders Otto; and with six children born out of wedlock, Stina would have been akin to an outcast. She probably also had to be “purified” by the church:[[9]] (1998-2), 93-114

In the eyes of the Swedish Protestant church the mother of an illegitimate child was not “pure” and could not take part in normal religious activities. According to the church law of 1686 she had to be purified. [After 1741] she was obliged to face only the minister and admit her sins. […] Purification was officially abolished in 1855, but continued on the local level for several decades. Illegitimacy was also a crime according to the State law of 1734. The punishment was usually a fine, which the man – if his guilt could be proven in court – was supposed to pay.

However, on 4 December 1802, Stina married farmhand Anders Isaksson in Agunnaryd, perhaps in an arrangement made by Anders Otto. The couple moved to Stina’s hometown, Tranhult, where they would have five children of their own. Two years later, Anders Otto gave them a monetary gift for his five surviving children with Stina, intended for their “food, clothes and upbringing” until they came of age. The gift amounted to 333 1⁄3 riksdaler, or the amount a male worker in Sweden received as a wage for about 10,000 hours of work.[[10]]

In the early 1800s, Anders Otto was involved in an incident at Bråna Guest House in Agunnaryd. The details are unclear; however, in 1802, a court ordered the plaintiff Swen Holmquist to pay a fine and reimburse Anders Otto’s legal expenses for the case.[[11]]

Anders Otto probably lived in Smedjemåla for the rest of his life, most likely with his son Göran. Anders Otto died on 2 September 1815 of old age – he was 75.

[[1]]: This was generally a rank of non-commissioned officer in the army.

[[2]]: Hans Högman, “The Allotment System – Sweden (3a),” http://www.hhogman.se/late-allotment-system-1.htm

[[3]]: Biografica, Microfilmed dossiers, Riksarkivet, SE/KrA/1051/003/P/14, image ID: A0066548_00390, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/bildvisning/A0066548_00390

[[4]]: Josef Henrik Theophil Rosengren, 1914. Ny Smålands Beskrifning [New Småland Description] Volumes 2-3 (Vexiö: Vexiö-bladets boktryckeri, 1914), 8, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=bKz3h4fVLksC

[[5]]: Born in 1771 in Tranhult to Jöns Jonasson and Svenborg Persdotter.

[[6]]: Nils William Olsson, “What’s in a Swedish Surname?” Swedish American Genealogist, vol.1, no.1 (1981), https://digitalcommons.augustana. edu/swensonsag/vol1/iss1/15; Anders Otto’s children with his wife, on the other hand, bore the family name Påhlman

[[7]]: Geoffrey Fröberg Morris, “Find the Unknown Father in Sweden,” familysearch.org

[[8]]: Ugglansryd was purchased by Baron AJ Raab and owned by the Raab family at least till the mid-1800s. It was eventually demolished in 1961.

[[9]]: Brändström Anders, “Illegitimacy and Lone-Parenthood in XIXth Century Sweden,” in Annales de démographie historique

[[10]]: A statement signed by the concerned parties in 1819 to be released from further claims provides details of the amounts that were gifted in 1804, and also mentions the children’s professions in 1819. The three daughters worked “in the service of others,” the eldest son was a shoemaker, and their second son was a hatmaker. Sunnerbo District Court Archives, Estate records and inheritances, Riksarkivet, SE/VALA/01582/F II/26 (1818-1819), image ID: C0112570_01026, https://sok.riksarkivet.se/bildvisning/C0112570_01026

[[11]]: Rolf Carlsson, “Tingsprotokoll Isak Adolf Bredendick – Historia från Odensjö,” http://odensjohistoria.se/dokument/11226bredendick.htm, accessed: 2 September 2022